I spent my last full day in Poland on an excursion from Lublin to the former site of the Bełżec extermination camp, eighty-five miles southeast near the Ukrainian border. The journey began with a cab ride from Jacek’s apartment to Wieniawa, Lublin’s university neighborhood, where I picked up a rental car at a local hotel. After winding past leafy city parks and students idling at bus stops, I merged onto a beltway and headed out of town. Lublin’s suburbs still flickered in the rearview mirror when I exited onto a two-lane road that I would follow for another seventy miles to the camp memorial and museum. Along the way, I cut across vast, rolling farmland while passing trucks and tractors crawling between small, roadside towns. Although this bucolic route is the main link between Lublin and Lviv, I had the sense of embarking into an obscure corner of Poland to visit a lesser-known Holocaust site.

Bełżec, however, had never been marginal to the Nazi regime.

Prior to Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 (“Operation Barbarossa”), the town of Bełżec stood at the frontier of the Nazi-Soviet partitioning of Poland imposed in September 1939. As an outpost of the General Government zone of Nazi-occupied Poland, Bełżec initially became the site of a labor camp where groups of mainly Jewish prisoners constructed borderland fortifications and infrastructure in 1940. The launch of “Operation Barbarossa” brought Soviet-occupied Poland under Nazi control, including the formation of the Galicia District of the General Government, which encompassed the cities of Lviv, Tarnopol, and Stanisławów and the lives of more than 600,000 Jews.[1]

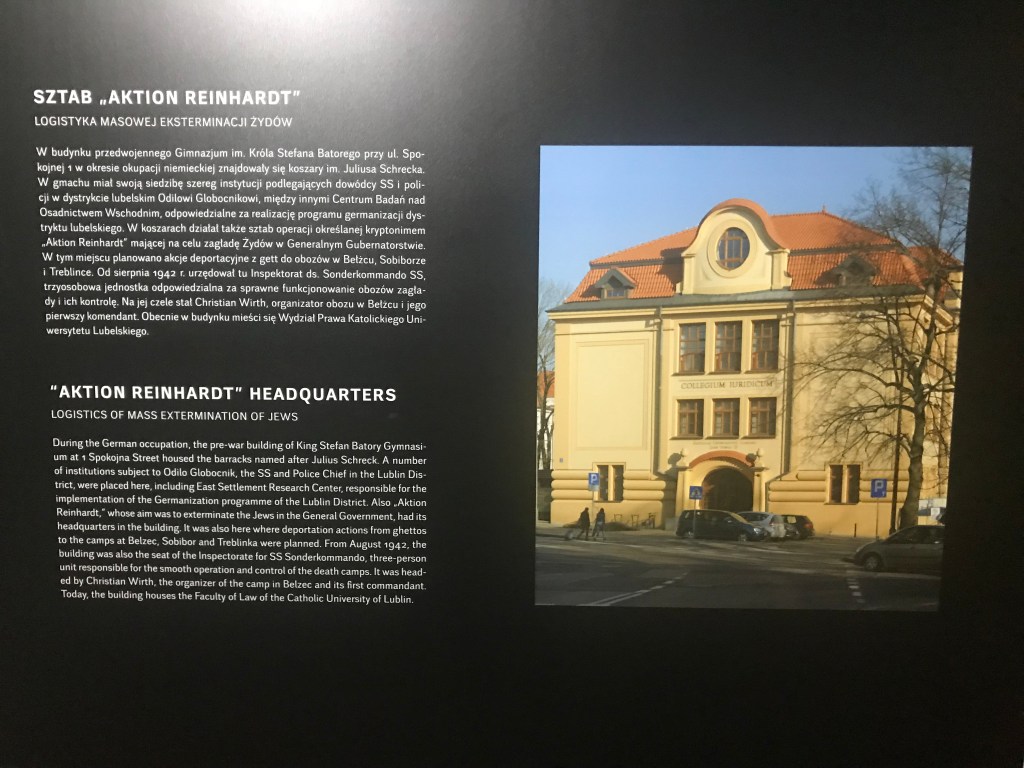

The ensuing mass murder of 1.6 to 1.735 million Jews in the General Government from 1942 to 1943 (“Operation Reinhard”) had deep roots in Bełżec.[2] While SS leaders coordinated the genocide from their administrative headquarters in Lublin, they developed a death camp in Bełżec that would become the template for the other “Reinhard” extermination facilities at Treblinka and Sobibór. More than half a million Jews perished at Bełżec, primarily from Galicia, during its nine months of principal operation from March to December 1942.[3] Bełżec’s proximity to railway connections spanning the Lublin, Kraków, and Galicia Districts of the General Government—a calculation not remiss to the perpetrators—was instrumental to the camp’s staggering lethality.

Despite its foundational role in the Holocaust, Bełżec is probably the least known of the major Nazi camps. Its relative obscurity has at least three main roots. First, there is an overdetermined association of the Holocaust with places like Auschwitz and Dachau, which have accrued voluminous popular and scholarly attention while overshadowing less familiar sites like Bełżec. As household names, they have made an impression on popular memory and forged well-worn paths of Holocaust engagement that nevertheless can be limited in scope and episodic in nature. Under such conditions, Bełżec remains the purview of the specialist.

Bełżec’s obscurity also derives in part from an extreme scarcity of known survivors who left behind testimonial accounts. Rudolf Reder and Chaim Hirszman are the only two known Jewish prisoner-workers at the camp who survived the war. Reder gave a short account of his experiences to the Jewish Historical Commission in Kraków, which they published in 1946. He also provided deposition in the lead-up to the trial of eight former SS camp personnel held in Munich in the mid-1960s. Meanwhile, Hirszman was murdered by members of an anticommunist underground in Poland just hours after his first meeting with the Jewish Historical Commission in Lublin in March 1946. As a result, Reder’s account remains the only complete survivor testimony about the camp and a little known one at that—an English translation first appeared in an academic journal in 2000.[4] One of the most insidious legacies of Bełżec has been the absence of a critical mass of survivors to speak out, bear witness, hold perpetrators accountable, and provoke sustained historical inquiry.

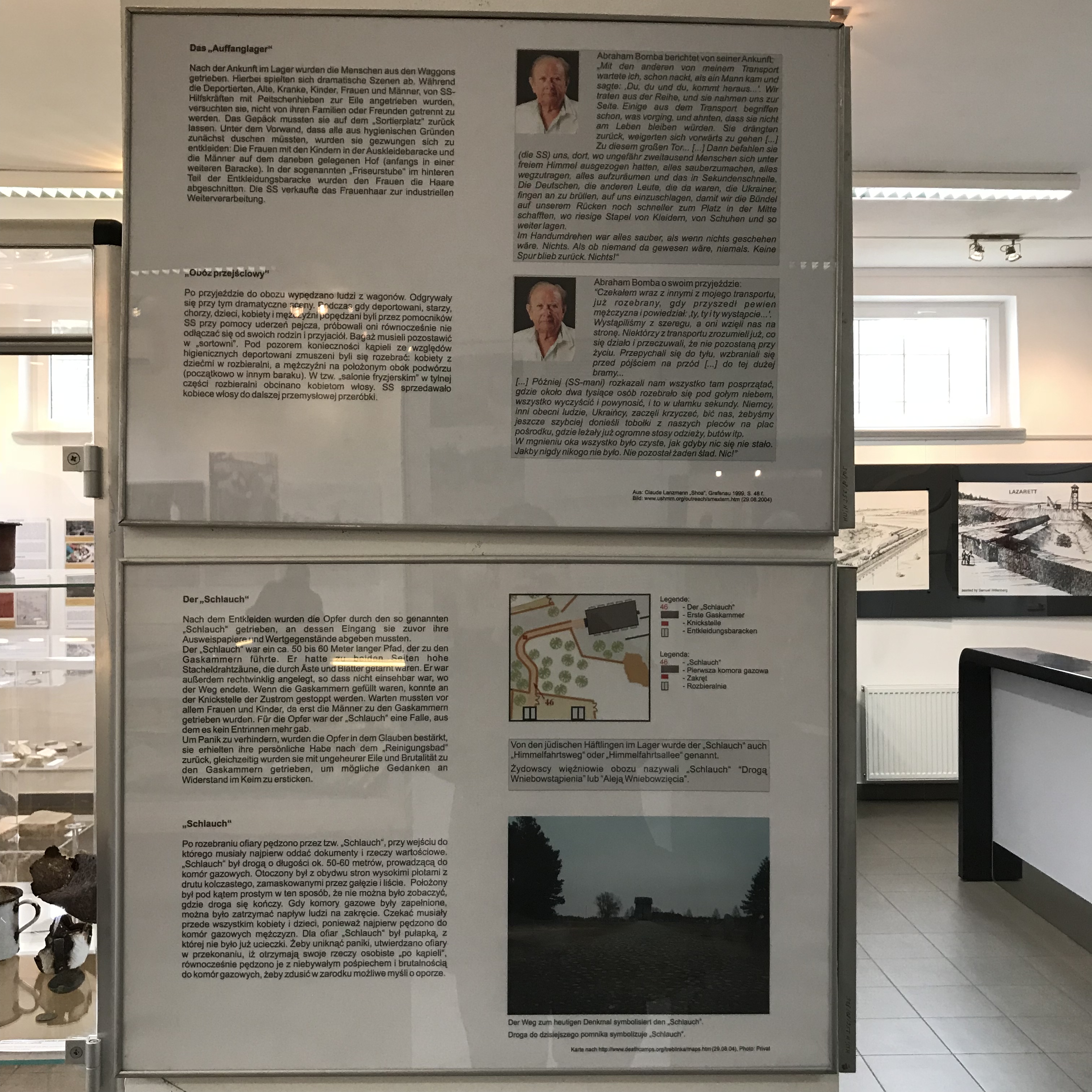

By contrast, the “Reinhard” camps of Treblinka and Sobibór are much more established in Holocaust history and memory. In 1943, successful uprisings at each camp allowed several hundred prisoners to escape, some of whom would survive the war, share their accounts, and testify at war crimes trials. Treblinka is also embedded in the wider history of the Warsaw Ghetto while Sobibór is often showcased as a pinnacle of Jewish resistance. Historical accounts of Bełżec are narrower in scope and usually emphasize its development and operation by the Nazi perpetrators since their records and courtroom testimonies are often the only archival materials available. Indeed, the most frequently discussed inside account of Bełżec comes from Kurt Gerstein, an SS officer who once visited the camp and witnessed an especially brutal gassing of Jews that took close to three hours due to breakdowns with the tank engine used for carbon monoxide.[5] Afterwards, Gerstein attempted to raise alarms with Swedish authorities and the Vatican while still working for the SS bureau charged with supplying Auschwitz-Birkenau and other camps with Zyklon B.

The overlooking of Bełżec and the preponderance of perpetrator vantage points when discussing the camp have traces in Lanzmann’s Shoah. The former site of the camp and the present-day town railway station make a fleeting, two-minute appearance in Shoah’s eighth hour. It occurs in the middle of a longer sequence about the Warsaw Ghetto that counterposes Raul Hilberg’s close reading of Adam Czerniakow’s diary with the calculated amnesia and pointed evasions of Franz Grassler, a former Nazi administrator of the Ghetto.

Czerniakow was a vocational teacher and Jewish community leader whom the Nazis appointed as the head of the Warsaw Ghetto’s Judenrat—a puppet Jewish council used to enforce Nazi decrees. Czerniakow’s daily diary, which he kept from the early days of the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939 until his suicide on the eve of the “Great Deportation” of over a quarter-million Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto to the gas chambers of Treblinka in the summer of 1942, provides unparalleled insights into the Ghetto’s history and his own untenable position as a guardian of Warsaw’s Jewish community and an implementer of Nazi decrees.

In the months leading up to the “Great Deportation,” Lanzmann and Hilberg consider how much Czerniakow might have known about the “Final Solution” and the deportation of Jews from other parts of Poland to Bełżec and Sobibór, which opened several months before Treblinka, starting with Bełżec on March 17, 1942. Hilberg indicates that Czerniakow had a keen sense of foreboding but might not have spelled everything out in his diary. Instead, Lanzmann uses his movie camera to fill in such gaps. First, he pairs a voiceover of Hilberg discussing Czerniakow’s distress over a sudden trip to Berlin made by the Ghetto Commissar Heinz Auerswald (Grassler’s superior) in January 1942 with present-day footage of the Wansee villa where the “Final Solution” conference was held. Even though he wouldn’t have had direct knowledge of this event, Czerniakow’s trepidation appears well-founded if not prophetic.

When Hilberg observes that Czerniakow made note of the deportation of Jews from ghettos in Lublin, Kraków, and Lviv in March 1942, Lanzmann cuts from Wansee to Bełżec. A slow pan reveals a disheveled, sandy hillside bordered by pine trees—the empty remains of the extermination camp. It is followed by a static shot of the same torn landscape but from a different angle, between stacks of tree trunks felled by loggers. The site appears to have been repurposed by the local timber industry rather than turned into a memorial. Lanzmann inquires if Czerniakow knew that the deportees had been sent to Bełżec. As the screen fills with clanking freight cars and the humdrum buzz of the town train station, Hilberg intones that Czerniakow didn’t specify destinations in his diary but he still might have been aware of the existence of death camps several months before the “Great Deportation” began in Warsaw. Czerniakow’s knowledge of Bełżec, in the final analysis, remains elusive.

The same might be said of the viewer’s grasp of Bełżec, albeit for a different reason.

While Lanzmann took an allusive approach to the Holocaust in Shoah, one that underlined the impossibility of direct representation and the distortions of “realism,” his tack with Bełżec is cursory at best. It’s a surprising move given his deep interest in the technical development of the “Final Solution” and the centrality of Bełżec to that process. Even in the vast archive of Shoah outtakes, there is only an additional twenty-two minutes of location footage from Bełżec and no evidence that he attempted to engage the locals as he often did at other “camp adjacent” sites in Poland. Indeed, he might have already had his sights set on Chełmno, the perennially overlooked first death camp, which, in a pathbreaking move, he made afocal point of Shoah’s first half. While Bełżec is not absent from the film, its passing treatment is a lacuna and missed opportunity.

Several decades later, the French filmmaker Guillaume Moscovitz would attempt to tie up some of the loose ends. His 2005 film, Bełżec, follows in Lanzmann’s stylistic footsteps and acts in part as an unofficial supplement and satellite of Shoah. Like Lanzmann, Moscovitz takes a nonlinear approach rooted in present-tense footage of the former site of the extermination camp and its environs. He interviews local residents of Bełżec, some of whom witnessed the genocide and had varying interactions with it. An elderly man recalls being placed on a labor squad by the Nazis to work on the camp’s construction, whose purpose he surmised in the process. An elderly woman continues rolling dough in a bakery that once supplied the camp with its daily rations of bread. An aging couple remembers the pleading for water that emanated from the trains waiting outside the camp and the pervasive stench of the pyres that burned for months. One man’s father created a series of paintings depicting scenes from inside the camp caught by his own surreptitious glances from a hillside.

And then there is the testimony of Braha Rauffmann—a Jewish woman deported from Lviv to Bełżec when she was seven years-old. After escaping the train, a local family hid her for two years inside a massive woodpile just steps away from the camp. Her young age coupled with the fact that her mother was originally from the town of Bełżec likely influenced her rescuers. When it was finally safe to pull her out, she had forgotten how to walk. Speaking before the camera, Rauffmann looks haunted and disembodied, her words rising like the shallow breaths of a still petrified child.

As in Shoah, the site of the extermination camp remains in a state of upheaval in Moscovitz’s film. A professor speaks of ongoing archaeological excavations to delineate the mass graves and uncover traces of former buildings. Local teenagers roam the grounds as if it were a park. Although Moscovitz is not an active, on-screen presence like Lanzmann, his translator does correct a young man who claims that 150,000 Poles died at the camp—the actual number was 150—an intervention that echoes Lanzmann correcting a former German schoolteacher that the number of victims at Chełmno (where she worked nearby) was 400,000, not 40,000. “I knew it had a four in it,” went her infamous reply.

When I arrived at the Bełżec Memorial and Museum after two hours of driving from Lublin, I only recognized the slope of the camp from Lanzmann’s film. The surface of that landscape, however, had undergone major transformations.

Before driving through a metal security gate that encircles the entire site and parking my car, I noticed a sign posted just outside the camp. It contained a map of the town highlighting points of interest and listed a municipal website with information about the town’s history and recommendations for tourists, all of which tended to dilute the proverbial elephant in the room. In addition to protecting and conserving the site, the security gate might inadvertently separate the camp’s history from that of the town, a de facto quarantine further underlined by the sign’s bid for tourists to linger in the area after paying their respects at the memorial. On the verge of entering a physical compartment, I felt signaled to compartmentalize.

After parking my car, I passed through another gate and walked onto the grounds. The former site of the camp is now dominated by an enormous, immersive memorial designed by Andrzej Sołyga, Marcin Roszczyk, and Zdisław Pidek. When it opened in 2004, two years after Moscovitz conducted his filming for Bełżec, it marked the culmination of almost two decades of collaboration between the Polish government and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC to conserve and update the site. The resulting installation is massive in scale and post-apocalyptic in appearance. The edges of the ragged hillside visible in Shoah have been reinforced with concrete retaining walls topped with jagged strands of rebarb. The slope itself has been filled with piles of slag, like the charred remains of a volcanic eruption. The walkway around the perimeter is inscribed with the names of cities, towns, and villages whose Jewish residents had been deported to the camp. Arranged chronologically, each name is written in Polish and Hebrew in oxidized metal along with the month and year of deportation. Collectively, they form a flat headstone around the remains of mass graves and long-effaced camp structures.

A long corridor lined with cobblestone cuts through the middle of the memorial with walls that gradually rise from a few inches at the entrance to upwards of thirty feet at the back. As one traverses the passageway, which traces the route to the gas chambers, the movement of air and sound evaporates as the memorial towers to even greater heights. An open-roofed mausoleum lies at the end. A stone wall has the words of Job carved into in Hebrew, Polish, and English: “Earth, do not cover my blood; let there be no resting place for my outcry.” The Hebrew version of the quote is written in the largest type at the bottom of the panel. Immediately below it, deep vertical gashes tear into the stone and encroach upon the Hebrew letters. Are these the frenzied scratches of victims crying forth for justice and remembrance? The erasing hand of the perpetrator? The amnesiac ravages of time? Perhaps all three. The memorial at Bełżec seeks to maintain tension rather than dispel it. It amplifies disorder to uncanny effect. It is at once unsettled and unsettling.

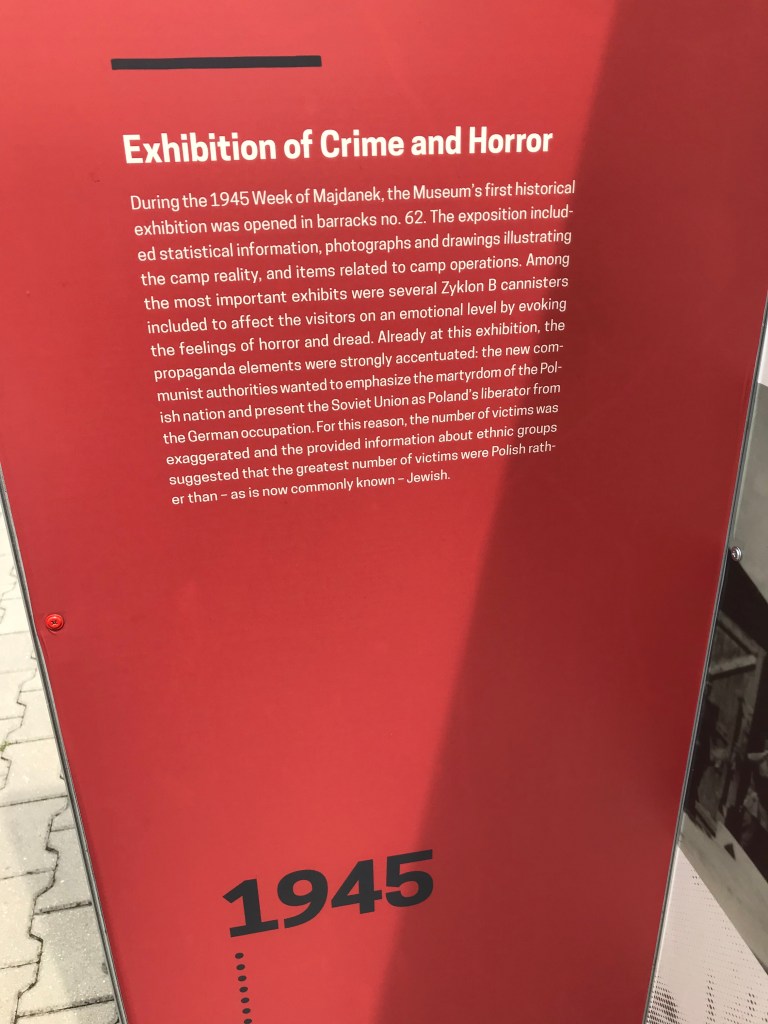

Another focal point of my visit was the camp museum, a rectangular, concrete slab that sunk into the landscape like a half-submerged bunker. The historical exhibition inside, largely organized by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, detailed the history of the camp and Operation Reinhard in English, Polish, and Hebrew. Based on the extant archival material, the display often emphasized the role of Nazi perpetrators. Photographs that the SS took of themselves were frequent. A plexiglass case contained a model of the camp building that held the gas chambers, a reconstruction based on evidence from the Bełżec trials and the written testimony of Rudolf Reder. An interactive, light-up map charted the Jewish communities deported to the camp during each month of its operation.

One panel in the exhibition caught my attention in particular. Among the documents and models was a small television screen whose frame had been fashioned to look rusty and metallic. A familiar figure seemed to flutter on an endless video loop, trapped in celluloid amber and displayed in perpetuity from a miniature prison cell inside the museum.

The clip came from Shoah.

One of the most striking scenes in Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah unfolds in a Bavarian pub in Munich’s medieval quarter. It surfaces almost two hours and forty minutes into the film and lasts just over four minutes. Like the segments I analyzed in my previous blog entry, part of its meaning is interwoven with the scenes that immediately precede and follow it. This sequence, however, also has a dramatic, standalone quality, like a miniature film within a film. Here, Lanzmann seems to venture into “caught-on-camera” investigative reporting, albeit in an artful flourish rather than in methodical accordance with TV news magazines like 60 Minutes and Frontline. Although it’s been overlooked in scholarly appraisals of Shoah and in Lanzmann’s own discussions of the film, it’s a scene that leaves a lasting impression on many viewers. When I fished out a copy of Lanzmann’s memoir, The Patagonian Hare, from a Hollywood record store several years ago, the cashier recalled the sequence with awe and I quipped that, “Michael Moore might owe his entire career to that scene.”

The sequence begins with the camera tracking forward at eye level through a backend staging area for the waitstaff of the Franziskaner Restaurant—a beer hall that sits in the shadow of Munich’s Residenz, a former palace of the Wittelsbach dynasts. The right side of the room is enclosed by a rectangular stainless-steel counter with a beer tap and a few wine bottles. A lighting box hovers above the counter, glowing with the slogan for a local Bavarian brewery like an icy halo: “Dein Bier Löwenbräu” [Your Beer, Löwenbräu]. The company’s regal insignia—a lion rearing on its hindlegs with tongue extended—is stenciled in white on blue wall tiles. Behind the counter sits a man pushing retirement age although his presence is obscured by the accoutrements of the barroom. His receding hair is slicked back and the collar of his white dress shirt is tucked into the edges of a gray cardigan. He gives the camera an apprehensive look while perching a cigarette in his right hand. Smoldering in the background, he is an easy-to-miss figure who seems to hide in plain sight. The camera lens is not aimed at him but rather fixes its gaze straight ahead toward the diners in the next room. The resulting exchange is one of mutual side-eyeing.

The camera passes beneath a rounded arch into the dining room, its double doors ornamented with diamond lattice windows. Chandeliers constructed from the tops of oaken beer barrels dangle from the ceiling while autumnal coats hang on racks at the foot of each table. Light blue tablecloths with white embroidery soften the wooden booths running in a parallel line. A few curious patrons turn toward the camera as it floats down the aisle. One man can be seen from behind wearing suspenders and a Tyrolean hat. As the camera approaches the end of the dining room, this long, wandering take is finally cut.

After a quick edit, a moment of disorientation ensues as the next shot is briefly obstructed by a passing waitress. As the camera pans from right to left (rather than tracking forward like the previous shot), the staging area of the restaurant returns to view. This time, the camera faces the counter and beer tap instead of moving past them at a perpendicular angle. Another waitress enters the shot and the camera pans back to the right slightly to observe her filling an ice bucket, which produces an asymmetrical frame filled by the waitress on the right and part of the beer tap on the left. The older man in the cardigan then steps into the left edge of the frame as he fills Weizen glasses with draft beer. Although the rear panel of the tap obscures his face, his eyes glance up at the camera each time he places a foamy, brimming glass on the counter. As if drifting towards a new figure of interest, the camera slowly pans back to the left in order to center the shot on the man and the beer tap. When he steps aside to retrieve a beer bottle from a nearby refrigerator, the camera turns again to keep him in view. It remains trained on him as he circulates about his workspace, even as waitresses enter the frame to whisk away glasses of beer to the dining room. He looks up periodically to see if the camera is still pointed in his direction. Indeed, he can’t seem to shake its attention.

In the subsequent shot, the camera’s dance of dissemblance around the bartender intensifies as Lanzmann enters the scene. At first, the camera follows a waitress walking over to the counter to rinse some glasses in the sink. Then it pans to the right as she places them under the beer tap in front of the man in the cardigan, who begins filling them. “Excuse me, how many quarts of beer a day do you sell?” asks Lanzmann in tentative German. Lanzmann’s right hand briefly enters the frame, pointing toward the beer tap, and the camera moves a few steps closer to capture the man’s response. He shakes his head, declines to look up, and waves off the question, mouthing the word nein. “You can’t tell me?” Lanzmann persists. The man steps to the right side of the counter and gestures for Lanzmann, whose head is now visible, to lean in: “I’d rather not. I have my reasons.” Resuming his post behind the beer tap, he ignores Lanzmann’s follow-up: “But why not?”

A waiter is now standing by to pick up an order. Lanzmann repeats his question about the amount of beer sold each day. The man exchanges a glance with the waiter and shakes his head. “Go on, tell him,” his coworker enjoins, vexed by the bartender’s refusal to answer a harmless, banal question. The peer pressure proves effective. He steps off to the side again and reports to Lanzmann, who now appears from the waist up, that it’s four hundred to five hundred quarts a day. “That’s a lot,” Lanzmann offers glibly. The man retrieves a bottle of beer from a refrigerator for the waiter, who pops the cap with a bottle opener tucked into his hand before carrying off a tray of drinks.

Lanzmann attempts to further break the ice: “Have you worked here long?”

“Around twenty years,” the bartender replies while inspecting his queue of order slips with the aid of thick glasses he has just put on.

“Why are you hiding your face?” probes Lanzmann.

He continues to tally the orders. “I have my reasons.”

“What reasons?” Lanzmann volleys.

With a slight shake of his head, he hangs the order slips on the wall, removes his glasses, and flashes Lanzmann a cold look: “Never mind.” Moving to the opposite end of the counter, he begins smoking a cigarette in a corner with his back to the camera.

His withdrawal is followed by a brief close-up of Lanzmann taking a black-and-white photograph out of his jacket pocket. He holds it up and asks, “Do you know this man?” The bartender turns toward Lanzmann, leans forward, and squints at the print. A close-up of the photo is edited in for the viewer’s benefit. It depicts a uniformed SS officer with glasses and a moustache. “Christian Wirth?” Lanzmann suggests to nudge the bartender’s memory. When he does not respond, Lanzmann identifies the bartender himself, adopting a similar tone of incredulity as the waiter: “Mr. Oberhauser!”

Oberhauser pulls back, his face and body tightening into a shrug at the unwelcome exposure. Turning away again, he continues smoking his cigarette and avoids the camera by standing behind a wall column.

Just a moment ago, Lanzmann requested inside information about the restaurant’s beer sales as a member of a French film crew presumably working on a production about Bavaria or beer or the like. Now, by dropping the pretense of naïve foreigner and resuming his identity as Holocaust filmmaker, he simultaneously breaches Oberhauser’s bartender façade. Oberhauser appears to have anticipated as much once he noticed the movie camera roving about the restaurant and drawing ever closer to him. Lanzmann’s ruse is a means of circling in with the camera lens even as he harbors few illusions that Oberhauser will discuss the actual subject that interests him. Still, he tugs at the veil of silence.

“No memories of Belzec? No? Of the overflowing graves?”

Not only does Lanzmann expose Oberhauser as a Nazi perpetrator from the Bełżec extermination camp, he also reveals his possession of camp secrets reserved to the SS. In a dramatic reversal of his earlier tack about beer sales, he now divulges inside knowledge of Bełżec’s horrors back to one of its main perpetrators. Yet the overflowing mass graves at Bełżec are more than a reference to a hidden history. They surge forth—unruly, repugnant, menacing—as memories that Oberhauser might avoid but cannot ultimately repress. Lanzmann’s words are a conduit of their return, calibrated with a “J’accuse!” on behalf of the victims.

Still, there is broader historical context worth developing beyond the inferences that Lanzmann expects the viewer to draw. Christian Wirth was the first commandant of Bełżec and a key figure in Operation Reinhard who brought a long resumé from the T-4 euthanasia program, where he pioneered the gassing of asylum patients with carbon monoxide. At Bełżec, he developed extermination protocols that became the model for other death camps, in particular the use of deception to lure arriving deportees into the gas chambers. Later, he worked from Lublin as an inspector for all three Reinhard camps.

Christian Wirth’s main assistant during Operation Reinhard was Josef Oberhauser. He also had a background in the T-4 program as a cremator of victims. At Bełżec, he supervised the camp’s construction and worked under Commandant Wirth, often serving as his liaison to Odilo Globocnik, the head of Operation Reinhard in Lublin. When Wirth became an inspector and relocated to Lublin in August 1942, Oberhauser followed with him. One of their first duties was restoring “order” to Treblinka after Globocnik removed its commandant, Imfried Eberl, for accepting more transports than the facilities could handle, which led to overflowing mass graves and piles of corpses around the camp. These events are described in Shoah by Franz Suchomel, a former SS officer at Treblinka whom Lanzmann filmed with a hidden camera, and Alfred Spiess, a prosecutor at the Treblinka trial in 1960. It is Suchomel who mentions that Wirth and Oberhauser already had experience dealing with over-capacitated mass graves at Bełżec, a discussion that appears in Shoah right before the restaurant scene.

After the dismantling and coverup of Bełżec, Treblinka, and Sobibór in 1943, Wirth, Oberhauser, and other Reinhard personnel were transferred to Trieste, Italy for anti-partisan activities, including the operation of the Risiera de San Sabba concentration camp. Wirth died in partisan warfare in May 1944 although some accounts allege that he had been killed by his own men. In the final days of the war, the British captured Oberhauser and in 1948 he received a fifteen-year sentence in Magdeburg for his role in the euthanasia program, which he served until 1956 when East German authorities released him as part of an amnesty for certain war criminals.[6]

Oberhauser soon faced charges from West German authorities for his role at Bełżec. Seven other indicted SS officers from the camp argued that they had acted under duress and emphasized fear of retribution from Wirth.[7] Since prosecutors lacked survivor witnesses and other evidence to challenge such defenses, the court dismissed the charges.[8] In Oberhauser’s case, he initially petitioned to have the charges dismissed by falsely claiming that Bełżec had already been covered in the Magdeburg trial.[9] When that effort proved unsuccessful, he sought to minimize his role at the camp by contending that he had only been at Bełżec to gather war materials and was only present for “experimental killings” in the camp’s early days.[10] Like his colleagues, he also pleaded duress.[11] His track record of promotion and preferential treatment from Wirth, however, undermined this line of defense. In 1965, the court convicted Oberhauser on five counts of complicity in the murder of at least 150 Jews, when he supervised the unloading of transports, and one count of complicity in the murder of at least 300,000 Jews for procuring building materials for the gas chambers.[12] He was the only Nazi official from Bełżec to receive a criminal conviction. After serving half of a 4.5 year sentence, he returned home to Munich.

“You don’t remember,” Lanzmann concludes, a pitch knuckled with disbelief. The camera focuses on the back of Oberhauser’s head, his profile hidden by the wall column he leans against with his left forearm. A shot of the restaurant’s exterior follows, capping the scene. This brief but memorable encounter now plays on a loop inside a museum gallery on the former grounds of the Bełżec extermination camp. Building on Lanzmann’s exposé, the curators have bound a key perpetrator to the very history, place, and culpability he sought to avoid.

To acquire perpetrator testimonies for Shoah, Lanzmann deployed an array of sting tactics including hidden cameras, false identities, uninvited visits, and, in the case of Oberhauser, a public waylay. He also made a point of disclosing key methods to the viewer alongside the snatched words and grainy visages of ex-Nazis. While his efforts might appear transgressive to some and questionable to others, Lanzmann has argued their necessity for giving an account of the Final Solution. After his initial tack of “frankness and honesty” with perpetrators “had been repaid with resounding failure,” he had to “learn to deceive the deceivers” as a “bounden duty.”[13] In his memoir, he underlined the physical and moral perils that such double-dealing entailed lest he be perceived as a zealous vigilante.

Viewing the Oberhauser scene was an arresting experience the first time I saw it almost a decade ago. Its appearance almost three hours into Shoah felt like a swell of adrenaline that paralleled the scene’s mounting tension. Amid the testimonial detailing of the Final Solution, here was an unstated cry for justice made in “real time.” Unable to provoke Oberhauser to speak of Bełżec, Lanzmann nevertheless captured his testimony of silence and evasion.

By rattling the bartender and the audience, Lanzmann exposes the past as far from settled even as the clink and chatter of everyday life carries on in the next room. Indeed, our relationship to the past might often be akin to dining room formalities: mannered, temperate, comfortable, limited in duration, and expectant of being both appetized and satisfied. Such politesse is more inclined to wave off the Holocaust than turn towards it, much less recognize its presence in the drinks arriving from the kitchen. And so Lanzmann must subvert it. His methods are more subtle than is often recognized, beginning with the long take that outlines the two rooms and establishes their connection.

When I first experimented with showing the Oberhauser scene in the college classroom, some students reacted to it as an affront to their sense of propriety: Lanzmann was being rude. One student even gave a hyperbolic “reenactment” of Lanzmann, making the filmmaker’s voice shrill and hysterical. Others asserted a proprietary notion of self that Lanzmann and his crew appeared to violate by pestering the nonreceptive Oberhauser on camera. In the eyes of the young, conflict-averse, and digitally saturated, what stood out was not the Holocaust, Bełżec, or postwar justice but decorum, personal privacy, and an unlikeable director.

At first, I interpreted such reactions as a call to provide more background information and historical context before screening the segment. They needed deeper academic foundations to better comprehend what they were seeing. Otherwise, they might be limited to emotional responses and knee-jerk reactions to a scene with palpable heat but no raised voices. I would have to provide them with new footing if they were to see beyond themselves and their customary viewpoints. And yet there seemed to be something about their resistance that went beyond straightforward pedagogical solutions and echoed the rawness of the scene.

The Oberhauser sequence in Shoah suggests that the Holocaust is not a settled past but a sutured present. The endless fractures and irrevocable voids produced by the Holocaust are constitutive of the present even if they are unrecognized. Indeed, they are often stitched over by partial, abbreviated narratives and the sense of finality implied by “moving on,” a call that hearkens to order and forgetting more readily than justice and reckoning. Oberhauser as bartender is less a clean break than a nondescript persona sutured over an SS leader. The stitchwork is tenuous and the guise depends on the complicit nonrecognition of others. After loosening its threads, Lanzmann begins to pull at the underlying reality. It’s not only an unwelcome gesture for a perpetrator seeking anonymity but also a direct challenge to the assumption that history is past and its study a pastime. Or, in the case of many of my students, an elective.

The deliberately fractured memorial at Bełżec might offer a new direction, one that underlines that void rather than attempting to fill it in with ready-made slogans, familiar narratives, or claims of national martyrdom (see #14 – From Warsaw to Lublin & Majdanek). Attending to Bełżec as an overlooked major site of the Holocaust entails much more than affording it a more prominent place in Holocaust literature. It means probing the roots of its marginalization and critically examining the habits that have held it—and much of the Holocaust itself—at bay. While some students cried foul at Lanzmann, others remained quiet, sitting with discomfort and uncertainty but also curiosity.

Epilogue

This blog essay is the final installment about my trip to Poland in 2018 in which I followed in the footsteps of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah to Auschwitz, Oswieçim, Łódź, Chełmno, Warsaw, Treblinka, Lublin, and Bełżec.

I recently returned from another trip to Europe that included visits to Holocaust sites, memorials, monuments, and museums in Poland, Latvia, Austria, Germany, and France. The material I gathered from this trip will be incorporated into my book instead of forming the basis for future blog essays. I still might share a few photos and insights from this trip as my project grows beyond a focus on Lanzmann’s Shoah and engages a wider set of issues in Holocaust memory and education.

It is worth mentioning that when I was in Munich a few weeks ago, I stopped by the Franziskaner restaurant where the encounter between Oberhauser and Lanzmann occurred many decades ago. The interior had been remodeled but the style was the same. The staging area and beer tap appear to have been relocated. The restaurant clientele was mostly tourists who sat outdoors and ordered Bavarian food. With ambivalence tempered by a sense of coming full circle, I sat down and ordered a beer.

[1] Yitzak Arad, The Holocaust in the Soviet Union (Lincoln, NE and Jerusalem: University of Nebraska Press and Yad Vashem, 2009), 274.

[2] Yitzak Arad, The Operation Reinhard Death Camps: Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, 2nd ed. (Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 2018), 440.

[3] Arad, The Operation Reinhard Death Camp, 440 and Arad, The Holocaust in the Soviet Union, 284.

[4] See Rudolf Reder, “Bełżec,” trans. M.M. Rubel in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Vol. 13, ed. Antony Polonsky (London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2000), 268-289.

[5] The most extensive analysis of the Gerstein case is Saul Friedländer, Kurt Gerstein: The Ambiguity of Good (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969).

[6] Michael S. Bryant, Eyewitness to Genocide: The Operation Reinhard Death Camp Trials, 1955-1966 (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2014), 63.

[7] Bryant, 57.

[8] Bryant, 62.

[9] Bryant, 63-64.

[10] Christopher R. Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939-March 1942 (Lincoln, NE and Jerusalem: University of Nebraska Press and Yad Vashem, 2004), 543.

[11] Bryant, 65.

[12] Bryant, 68.

[13] Claude Lanzmann, The Patagonian Hare, trans. Fred Wynne (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012), 449.

The Church of the Birth of the Virgin Mary in Chełmno nad Nerem, Poland

The Church of the Birth of the Virgin Mary in Chełmno nad Nerem, Poland The rental car: a Renault Clio from Avis

The rental car: a Renault Clio from Avis Views of the Ner River and surrounding countryside

Views of the Ner River and surrounding countryside The museum entrance in the village of Chełmno

The museum entrance in the village of Chełmno Efforts to excavate and preserve the foundations of the mansion are ongoing.

Efforts to excavate and preserve the foundations of the mansion are ongoing.

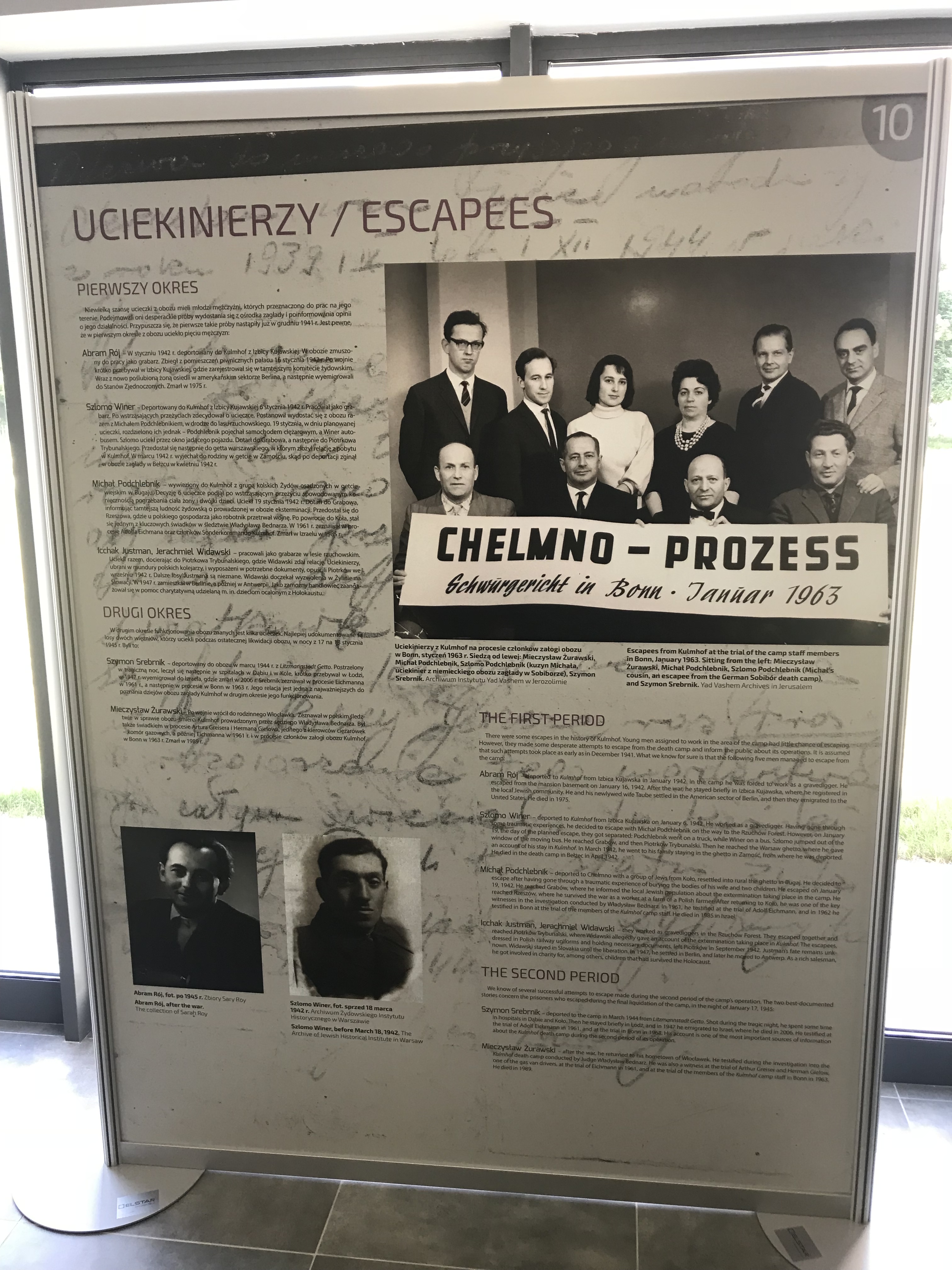

Simon Srebnik can be seen on the bottom right of the group photo.

Simon Srebnik can be seen on the bottom right of the group photo. A path in the Rzuchów forest leading to the main site of Chełmno’s mass graves. Srebnik and Lanzmann are seen walking here in the opening minutes of Shoah.

A path in the Rzuchów forest leading to the main site of Chełmno’s mass graves. Srebnik and Lanzmann are seen walking here in the opening minutes of Shoah. The site of one of Chełmno’s mass graves in the Rzuchów forest

The site of one of Chełmno’s mass graves in the Rzuchów forest The Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary

The Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary The front doors were open but access to the sanctuary was closed.

The front doors were open but access to the sanctuary was closed. “Monument to the Victims of Fascism” (1964)

“Monument to the Victims of Fascism” (1964) Memorial for Austrian Roma Sinti deported to the Łódź ghetto and later murdered at Chełmno (2016)

Memorial for Austrian Roma Sinti deported to the Łódź ghetto and later murdered at Chełmno (2016)

Bike riding in Brooklyn, New York

Bike riding in Brooklyn, New York New Hampshire in the late 1980s

New Hampshire in the late 1980s Adirondacks, New York in 2019

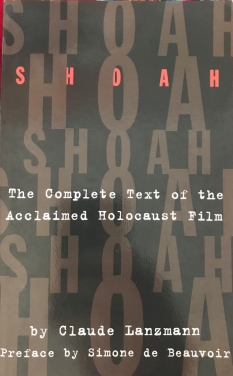

Adirondacks, New York in 2019 The transcript of Shoah

The transcript of Shoah Camp reading

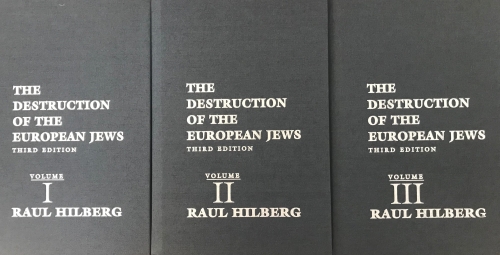

Camp reading Hilberg’s classic work

Hilberg’s classic work Hilberg’s 1996 memoir

Hilberg’s 1996 memoir Self-sustaining farm in Charlotte, Vermont

Self-sustaining farm in Charlotte, Vermont University of Vermont, Burlington

University of Vermont, Burlington Billings Library, University of Vermont, Burlington

Billings Library, University of Vermont, Burlington Hilberg’s former home in Burlington, Vermont featured in Shoah

Hilberg’s former home in Burlington, Vermont featured in Shoah

The interior gate of Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery (above) and a restaurant near Piotrkowska Street (below).

The interior gate of Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery (above) and a restaurant near Piotrkowska Street (below). Mundo Hostel, Kraków – I launched this website there!

Mundo Hostel, Kraków – I launched this website there! Street signs in Bałuty

Street signs in Bałuty The Piotrkowska Centrum tram station at the intersection of Piłsudskiego and Piotrkowska in Łódź

The Piotrkowska Centrum tram station at the intersection of Piłsudskiego and Piotrkowska in Łódź Piotrkowska Street, Łódź

Piotrkowska Street, Łódź Starbucks at Manufaktura, Łódź

Starbucks at Manufaktura, Łódź The cemetery gate near Bracka and Chryzantem, Łódź

The cemetery gate near Bracka and Chryzantem, Łódź A sign for self-guided walking tours through the Litzmannstadt Ghetto. This sign was near Manufaktura, which is also located in Bałuty.

A sign for self-guided walking tours through the Litzmannstadt Ghetto. This sign was near Manufaktura, which is also located in Bałuty. Radegast Station, Łódź

Radegast Station, Łódź Entrance to Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery on Zmienna Street

Entrance to Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery on Zmienna Street The Pre-Burial House in Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery

The Pre-Burial House in Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery Memorial plaques inside the cemetery’s interior wall

Memorial plaques inside the cemetery’s interior wall Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery

Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery

Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery

The ghetto field in Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery

The ghetto field in Łódź’s Jewish Cemetery Broken tombstones in the Jewish Cemetery of Oswieçim, Poland

Broken tombstones in the Jewish Cemetery of Oswieçim, Poland Pana Pietyra, a resident of Oswieçim, Poland

Pana Pietyra, a resident of Oswieçim, Poland Oswieçim, Poland

Oswieçim, Poland Oswieçim, Poland

Oswieçim, Poland Oswieçim, Poland

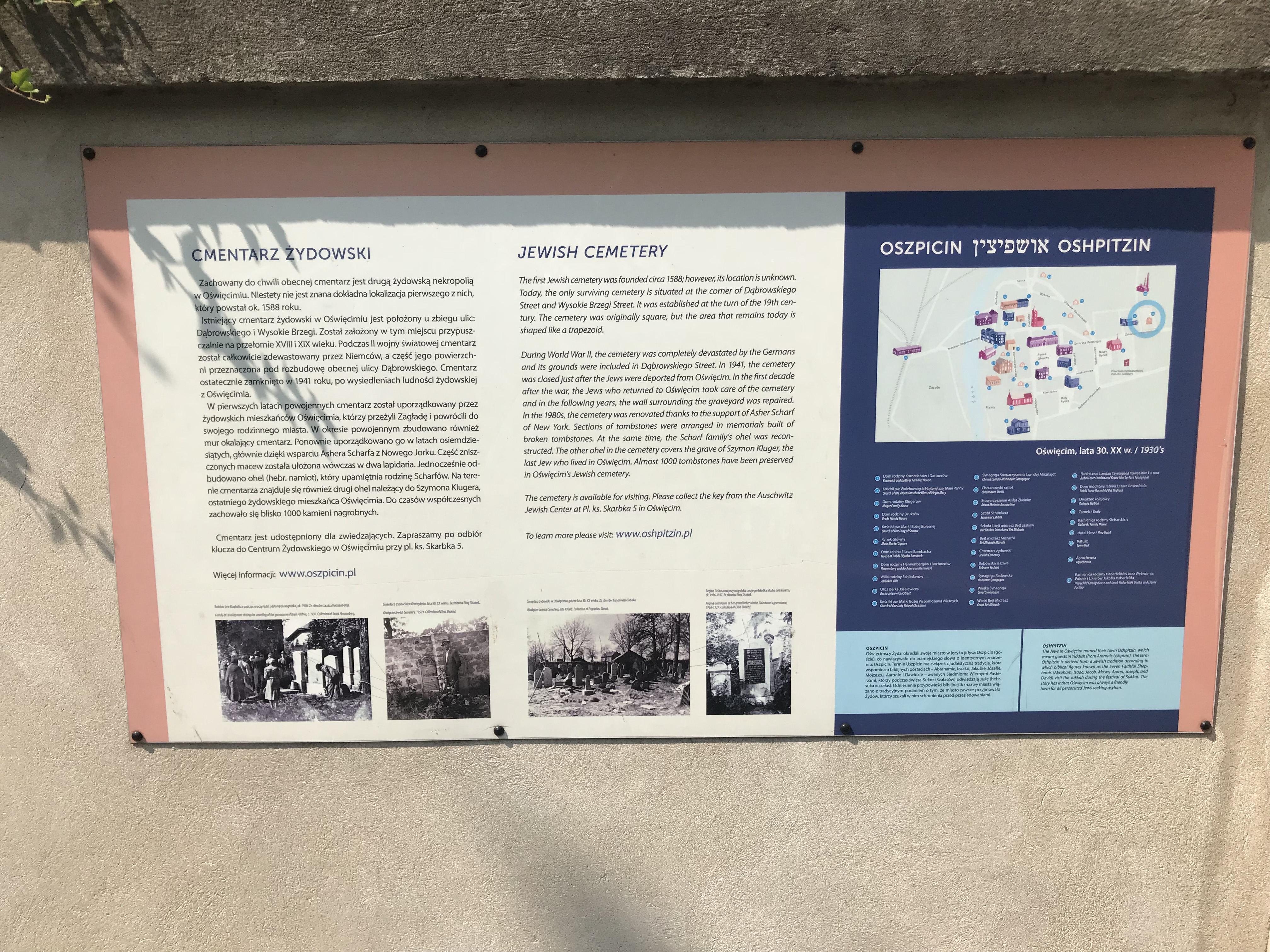

Oswieçim, Poland Outside the Jewish Cemetery, Oswieçim, Poland

Outside the Jewish Cemetery, Oswieçim, Poland

The Jewish Cemetery, Oswieçim, Poland

The Jewish Cemetery, Oswieçim, Poland The Jewish Cemetery, Oswieçim, Poland

The Jewish Cemetery, Oswieçim, Poland

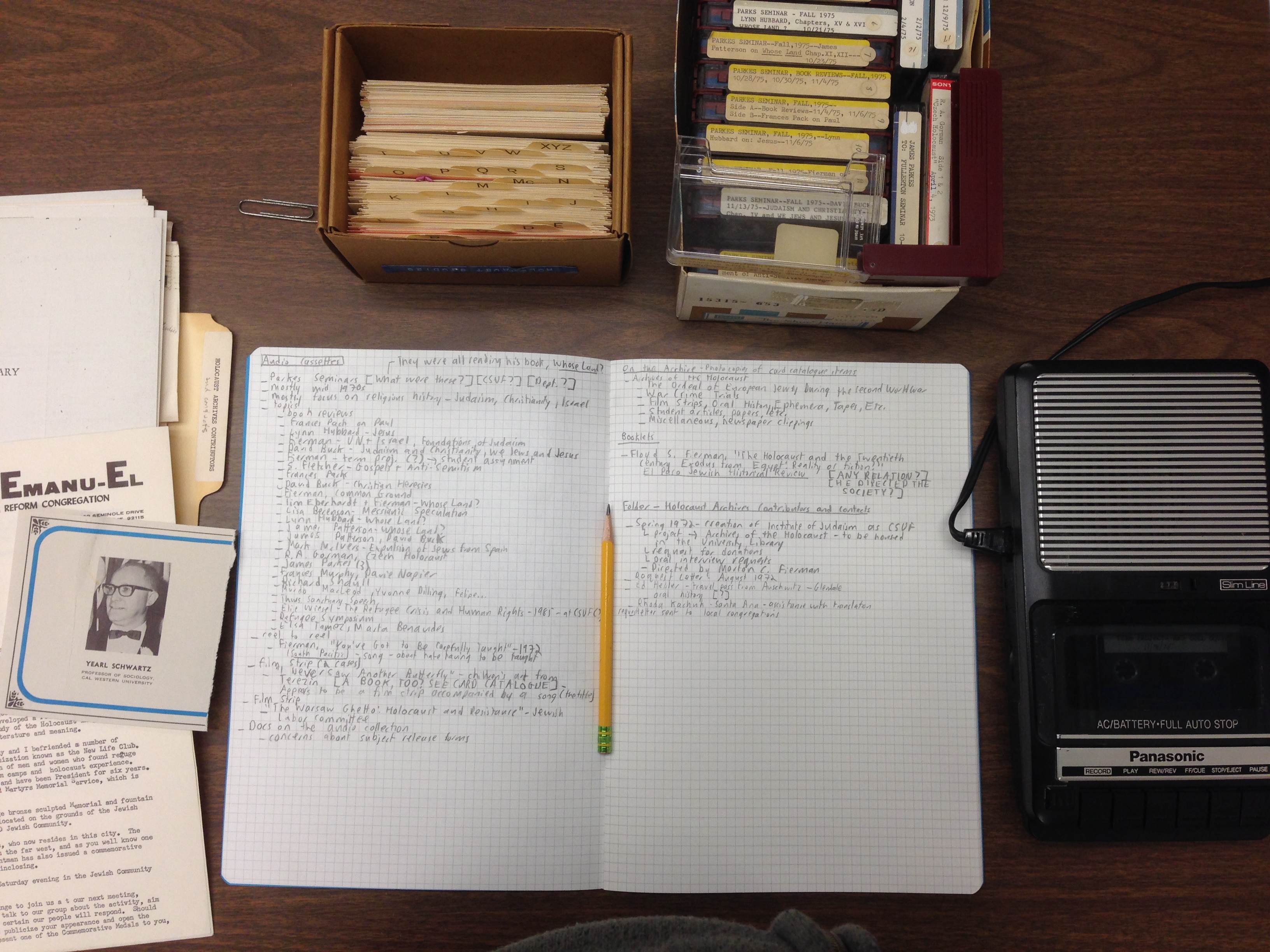

Working with the Archives of the Holocaust at Cal State Fullerton.

Working with the Archives of the Holocaust at Cal State Fullerton. Audio cassettes from the Archives of the Holocaust at Cal State Fullerton.

Audio cassettes from the Archives of the Holocaust at Cal State Fullerton. A venue for L.A.’s Chantal Akerman retrospective in Spring 2016.

A venue for L.A.’s Chantal Akerman retrospective in Spring 2016.

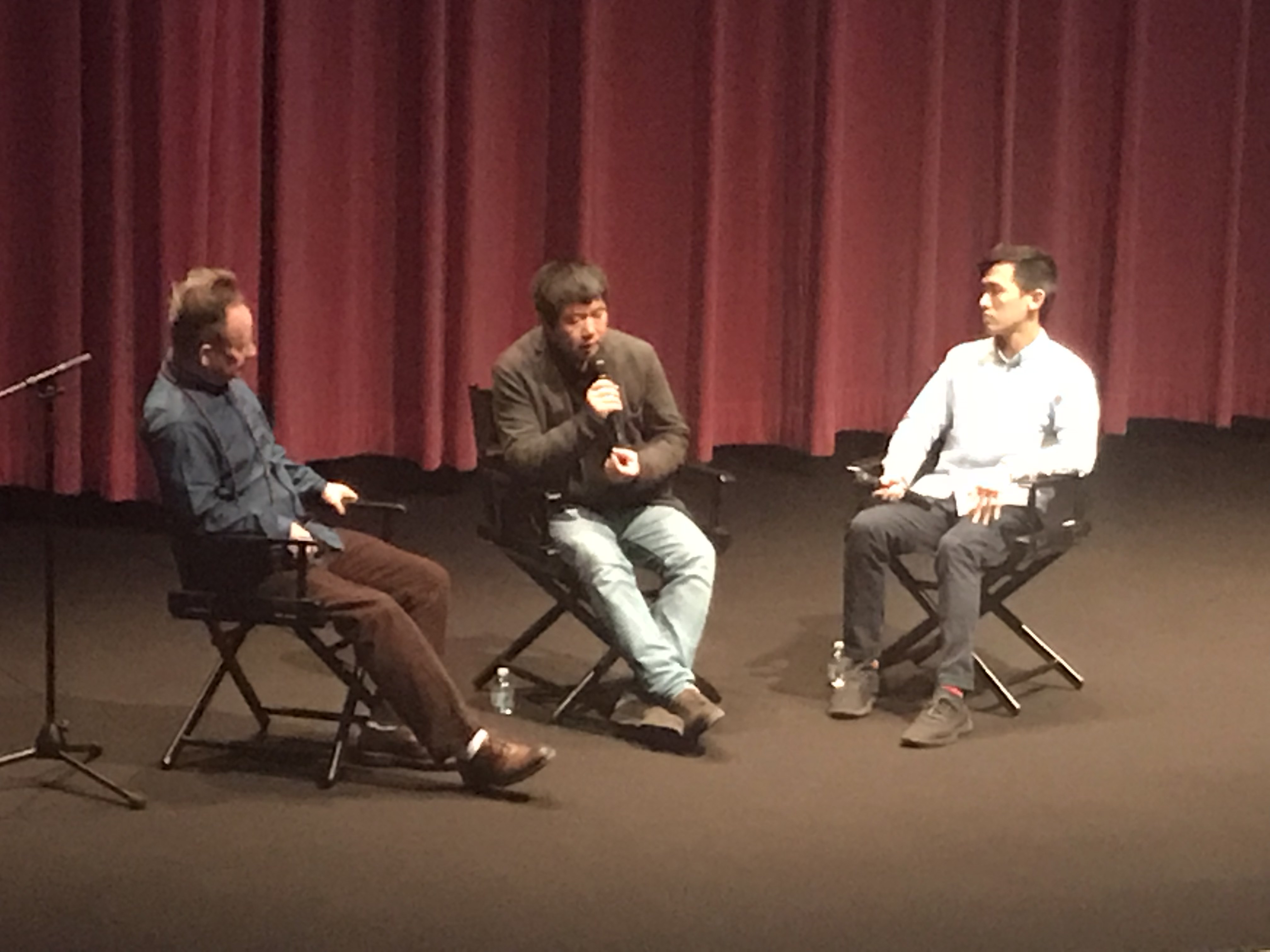

Director Wang Bing (center) at the Billy Wilder Theater with Peter Sellars (left) and a UCLA student translator (right).

Director Wang Bing (center) at the Billy Wilder Theater with Peter Sellars (left) and a UCLA student translator (right).