At the end of the platform, at right-angles to the tracks, nailed to two posts set in concrete, was a signpost bearing the name Treblinka on either side so travelers could see it from either direction. Treblinka was nothing but a ghost station: as I stood petrified on the platform, attempting to come to terms with the enormity of what I was witnessing, trains passed, some hurtling straight through, others stopping to load and unload passengers. [1] – Claude Lanzmann * * * I am naturally drawn to the scenic route.

It’s a predilection seemingly inscribed on the soles of my feet, where it leaves testimonial blisters. I hear its ancestral rumble as I imagine my great-grandfather cutting his motorcycle across the state line at dawn for breakfast at a mountain lodge, bending and weaving his way through the hidden corners of the suburban weekend. As a child, I remember absorbing its languorous rhythm on Saturday afternoons in the bob and sway of a small sailboat tacking upriver as my father surfed us through the frothy wake of passing motorboats. Many years later, my own trailblazing once led me from a bike ride around a sunny, pastel village to the discovery of a seaside trail, which in turn led to a scramble down a toothy cliff and into the emerald glow of a Mediterranean grotto.

The scenic route is more than the proverbial leisurely stroll. It is a state of being in which the exigencies of time and purpose are temporarily held in abeyance. By following its contours, we merge with a rhythm and logic beyond our own design and open ourselves to being imprinted by the world. Rather than finding what we are looking for, that which seeks us is given the opportunity to reveal itself. The world must speak through us if we are truly to have anything to say. We are more vehicle than driver. To wander the scenic route is to invite the world to interrupt us so that we might better know our place within it.

Such a lesson was not lost on Marcel Proust. The narrator of his monumental work, In Search of Lost Time, finally achieves his long-delayed self-actualization as a writer in the final volume of the novel after nearly falling on his rear end in a Parisian courtyard. As he walks pensively toward the entrance of an aristocratic soirée, he fails to notice an oncoming car. The cry of the chauffeur prompts him to step back sharply to avoid the car but he stumbles over some uneven paving stones behind him in the process. Fortunately, he is able to regain his balance and avoid a nasty fall. This seemingly unremarkable episode, however, triggers a much more consequential set of realizations.

As the narrator recovers from his near fall and stands on the uneven cobblestones, he experiences an unforeseen, radical shift in consciousness. Perennial doubts that had occupied his mind up to that moment—about his talent as a writer, about the significance of literature itself—suddenly evaporate. Elation surges within him as opaque images unfurl in his mind. These visions, he soon realizes, are a lost memory of standing on uneven stones inside St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice many years ago. That long-forgotten physical sensation, which scarcely registered to him then, now resurfaces as a portal of time travel back to an earlier self and its unprocessed archive of impressions. By gaining access to his raw past, he transcends his sense of personal limitation and finally commits to writing, the result of which is revealed to have been In Search of Lost Time all along. The entire seven volumes of Proust’s novel might thus be interpreted as the story of a stumble and the restoration of the circuitous path that led to it.

From this brief sketch of what is arguably the decisive episode in Proust’s magnum opus, I’d like to draw several lessons. First, the scenic route fertilizes the artistic process, much like the piles of bison manure I frequently encountered along the trails of Catalina Island this summer. Whether the “scenic route” represents an obscure road or a meandering life, it churns up contemplative space and nutrient-rich experiences that nurture and refine the creative spirit. Second, the harvesting of that journey occurs unexpectedly, often in a state of flux rather than by force of will or reason. The world might actually be throwing us into alignment precisely when we seem to lose our footing within it. In that awkward, uneven state, the door to creative self-realization “opens of its own accord.”[2]

Finally, Proust locates the deepest recesses of memory in physically embodied experience rather than the mind. As the narrator reenacts his backward stumble and unlocks its association with St. Mark’s, he observes that, “the supposed snapshots taken by my memory [of Venice] had never told me anything.”[3] At the surface level, memory often operates like a camera that doesn’t merely record but actively creates “memorable moments.” It is a self-aware, conventional process that strands Proust’s narrator in the cul-de-sac of the “official story.” His near fall in the courtyard, however, inadvertently resurrects a hidden trove of past impressions long-since evaporated from his conscious mind but quietly registered in his physical body. This restoration of “lost time” affirms the consistency and value of his life, his vision, and his voice.

What does this meditative detour through Proust and the scenic route have to do with Lanzmann’s Shoah and my visit to Treblinka?

Quite a lot, actually.

Lanzmann experienced his own Proustian moment during his first visit to Treblinka that would prove decisive for Shoah.

Already four years into his project, Lanzmann made an obligatory first visit to Poland in March 1978. Even though Shoah’s indelible depiction of place is foundational to its power as a statement on the Holocaust, the role it would play was not immediately apparent to Lanzmann as he notes, “I arrived [in Poland] full of arrogance, and convinced I was coming only to confirm that I had not needed to come.”[4] Shortly after landing in Warsaw, he met up with translator Marina Ochab, rented a car, and headed straight to Treblinka. Exploring the memorial site for several hours produced little effect on him other than a needling disquiet for having failed to be moved.

Unwilling to resign himself to mounting self-criticism, Lanzmann returned to his car with Ochab and began driving “aimlessly” along the perimeter of the camp. [5] The road eventually led them into the neighboring villages, which sparked a series of mounting realizations for Lanzmann. As he exchanged glances with the locals from behind the steering wheel, he recognized that many of the older residents likely witnessed the camp in operation. His subsequent sighting of the Treblinka village sign cut through the mythological veneer of the place-name he so often encountered in the pages of his research. The frayed distinction between past and present all but collapsed when he stood on the platform of the Treblinka train station and observed passengers disembarking. Reflecting on this moment decades later, Lanzmann compared himself to an exploding bomb.

Like Proust’s narrator, Lanzmann discovers his artistic voice through an accidental encounter with a hidden, dormant past that he feels duty-bound to articulate. Initially, both are confronted by self-doubt and a sense of inner limitation based on their perceived failure to self-actualize with the world. In response, they openly roamed and aimlessly wandered. Taking the scenic route loosened the grip of consciousness and allowed them to expand with the unfolding landscape. For Proust’s narrator, the act of mergence is an awkward stumble that breaches an unseen, embodied history. For Lanzmann, the revelation of overlooked traces of the Holocaust hiding in plain sight detonates his creative vision for the film. Both figures are time-bombs who throw themselves into the production of timeless, monumental works of art.

Upon leaving the Treblinka train station, Lanzmann launched into action by interviewing local villagers who remembered the camp. That day, he met Czesław Borowi, a middle-aged farmer whose land directly abutted the train tracks near the station. Lanzmann and his crew would return to film him several months later. His somewhat bemused recollection of backed-up trainloads of Jewish victims waiting next to his fields for hours if not days before being uncoupled and pushed into the camp on a rail spur would earn him notoriety in Shoah.

Acting on a local tip, Lanzmann and Ochab next headed to Małkinia and awoke Henryk Gawkowski and his wife late at night. Gawkowski was a Polish railway worker who drove trains of Jewish victims to the village station and then into the camp itself, receiving extra rations of vodka to aid the completion of this horrendous task. Following a conversation that wound into the early morning hours, Lanzmann returned in the summer to film Gawkowski driving a locomotive between Małkinia and the village station as a line sketch reenactment of the past.

Today, the railway between Małkinia and Treblinka no longer exists.

I made this discovery while walking five miles from Małkinia station to the camp on a rainy afternoon in June.

Still dazed from the conversation and watered-down vodka on the train from Warsaw [See “Treblinka (Part 1): The Train to Małkinia”], I rambled along Road 627 as misty raindrops collected in my hair and passing trucks kicked up a cloudy spray. Crossing the Bug River, I entertained vague recollections of the Napoleonic Wars and Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Later, I would read of SS officers cooling off in the river during the scorching summer months while the bodies of would-be escapees from the train lay scattered in the fields next to the track.

After the bridge, the pedestrian path diverged from the road and led me to the outskirts of Treblinka village. Wood-splintered barns and farmhouses cast ghostly eyes through the cover of trees. A passing car on a dirt road paused to observe a tourist getting his bearings. Eventually, the trail returned to the main road and a sign in brown lettering pointed to the entrance of the Treblinka camp.

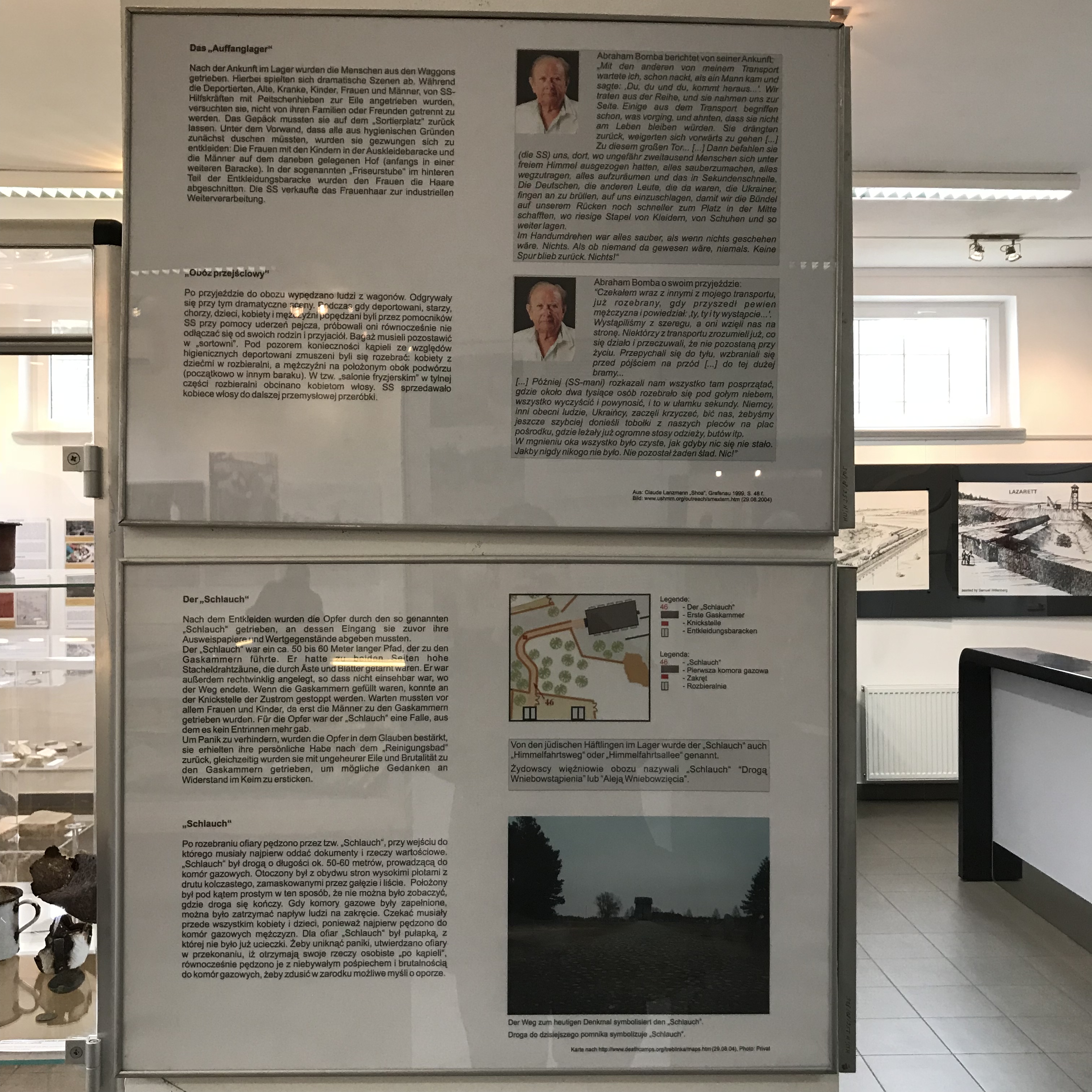

A cobblestone driveway led into the woods, winding past small memorials that seemed to hint at the enormity of what lay deeper within. A comment book inside a visitor kiosk revealed that a group of students from UNC Chapel Hill had visited just a few days earlier. On the far end of the parking lot, a small museum recounted the history of the camp and highlighted recent archaeological excavations around the site.

The museum exhibition also featured a panel with a photo of Abraham Bomba. A Polish Jew deported to Treblinka from the Częstochowa ghetto in southern Poland, Bomba lost his wife and infant son shortly after stepping onto the station platform inside the camp. A barber by trade, the camp officials eventually inducted him into the Sonderkommando (a special detail of prisoners forced to work at the gas chambers, crematoria, and mass graves). Bomba’s task was cutting women’s hair moments prior to their death in the gas chamber.

Abraham Bomba is one of the most unforgettable figures in Shoah. According to Lanzmann’s memoir, he was also one of the most difficult interviewees to track down—at one frenetic point in his search, Lanzmann knocked on all the doors in a Bronx apartment building. After finding him in upstate New York, Lanzmann had to trace his whereabouts again two years later, this time to Israel where he filmed him. Bomba speaks in two main sequences in Shoah: in the first, he sits on a terrace in Jaffa and describes his arrival and first night at the camp; in the second, he engages in a dialogue with Lanzmann about his experiences in the Sonderkommando while cutting a man’s hair in a barbershop.

Bomba’s first appearance in Shoah contributes to an extended sequence about the arrival process at Treblinka that interweaves testimonial statements from two survivors of the camp (Abraham Bomba and Richard Glazar) and the recollections of local Polish eyewitnesses (including Czesław Borowi and Henryk Gawkowski). The viewer is introduced to Treblinka aboard a locomotive driven by Gawkowski from Małkinia to the village station. As the steam engine grinds to a halt, the camera lingers on the station sign, echoing Lanzmann’s explosive first visit to the site while conjuring the viewpoint of arriving victims peering through the slats of the cattle cars in a desperate attempt to orient themselves and know their fate.

The long wait in the village before the final push into the camp produced scenes of tragedy and farce. Gawkowski, Borowi, and the villagers imitate a throat-slitting gesture they surreptitiously made toward the train cars, an alleged warning to the victims that inescapably bears the sting of mockery. Meanwhile, several railway workers share wrenching memories of Ukrainian guards who killed would-be escapees and randomly shot into the cars out of their own frustration. Bomba himself recalls the joy of some of the Poles who witnessed the deportations in Częstochowa and the confusion during his arrival at the Treblinka death camp. Immediately after being selected for work, Bomba helped clear the suitcases and personal belongings left behind on the platform, moving quickly to avoid the blows of the guards. Only later in the day did he realize the fate of his family and the other deportees.

Bomba’s second appearance in Shoah is one of the most famous and frequently discussed segments in the entire film. It occurs at the beginning of Shoah’s second half, preceded by an excerpt from a secretly taped interview with Franz Suchomel, a former SS guard at Treblinka, who sings the camp song taught to the prisoners for the amusement of their tormentors, which he cannot help but display once again while reciting it. The subsequent scene with Bomba unfolds over eighteen minutes as he slowly cuts a man’s hair in a crowded barbershop in Jaffa. At first, Lanzmann poses technical questions about his role as a women’s haircutter at Treblinka, including an initial period in which the barbers worked directly inside the gas chamber before the door was sealed. When asked about his first impressions of the situation, Bomba demurs mechanically that he had been given a job to do.

Bomba begins to crack when Lanzmann asks him to imitate the gestures of cutting the women’s hair on the man sitting before him. Bomba’s voice quickens as he says, “We did it as fast as we could.” Then he flinches and turns away in the middle of moving the scissors demonstratively around the man’s head. When Lanzmann returns to the question of his first impressions, Bomba replies distantly, “You were dead. You had no feeling at all.” As if the grip of his defense mechanism had just loosened, he then shifts to the first-person and says to Lanzmann, “As a matter of fact, I want to tell you something that happened.”

Bomba recalls encountering women he knew from Częstochowa at the gas chamber. “What could you tell them?” he asks rhetorically, underlining the futility of the situation while alluding to his own personal devastation. As his memories surface more freely, Bomba falls silent when remembering another barber on the Sonderkommando whose wife and sister showed up at the gas chamber. His eyes water and a stray teardrop rolls down his cheek. Eventually, at Lanzmann’s gentle but firm supplication, he completes the story with a broad statement about trying to do the best for loved ones under impossible circumstances.

Like Proust’s narrator, Bomba’s embodied memory is breached by the uncanny repetition of a physical movement. The backward stumble in a Parisian courtyard and the flurry of scissor snips in an Israeli barbershop resurrects specific moments from the past: standing within St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice and standing within a gas chamber in Treblinka. Beyond the widely contrasting nature of these memories, it is worth noting the precarious circumstances of their evocation. For Proust’s narrator, the return to Venice is the serendipitous outcome of near disastrous collisions with the car and the pavement. For Bomba, returning to his repressed trauma (and the memory of the victims entwined with it) is a tremulous negotiation of simultaneous urges to bear witness and remain silent. In Shoah, this conflict is externalized (and thus partly mitigated) by Lanzmann’s prompting as an interviewer along with the mise-en-scène of the barbershop providing a conduit of memory. While some have interpreted Lanzmann as strong-arming Bomba in this scene, such a critique risks occluding Bomba’s agency and investment in the exchange. Upon recovering his voice, he reminds Lanzmann, “I told you today was going to be very hard.”

Bomba remained on my mind as I began wandering the former grounds of the camp. Since the Nazis liquidated Treblinka in the autumn of 1943, no original structures remain. The memorials on the site commemorate the victims and punctuate an effaced landscape with a semblance of historical texture. The final two-hundred meters of the railway spur leading to the arrival platform is marked by dozens of rectangular, granite blocks embedded in the ground equidistantly to resemble train tracks. In Shoah, Lanzmann extends the metaphor by tracking the camera over the blocks to simulate the perspective of arriving victims.

The central memorial at Treblinka is an eight-meter obelisk surrounded by seventeen-thousand granite shards set in concrete that might be characterized as a post-apocalyptic cemetery. Positioned near the original site of the gas chambers, the obelisk is inscribed with a menorah near its top on one side and abstract, fragmented tangles of human forms on its other. The words “never again” appear in several languages on an adjacent block. A procession of large stones connecting the arrival platform to the obelisk are carved with the names of countries whose Jewish citizens perished at Treblinka. Several hundred granite shards beyond the obelisk bear the names of Polish cities, towns, and shtetls whose Jewish communities faced deportation and death at the camp.

I opened up a map I had picked up at the visitor kiosk and began tracking down the stone for Częstochowa. In Shoah, Lanzmann cuts to this memorial shard immediately after Bomba regains his voice and completes his story. It’s a powerful coda that personalizes the Częstochowa memorial while simultaneously indicating an infinitude of lost voices from that community and beyond. The value of individual testimony and the incalculable losses of the Holocaust amplify one another in this moment of silence.