During my long weekend in Warsaw, I often lingered at dusk looking out the window.

Leaning on the sill of my third-story perch at the corner of Nowolipki and Karmelicka streets, I studied the tree-lined sidewalks and drew imaginary constellations from the curtained glow of neighboring apartments. The world just beyond my room’s picture window seemed to resemble a college campus, an impression encouraged by the shared student flat where I was residing. Communist-era apartment blocks strummed a similar chord to the well kept but drab dormitory villages found at state universities. Impervious to nostalgic embroidery, they cast an impassive gaze over the endless cycle of residents passing through them. As a tourist swept up in the latest rotation, I looked out as slabby faces peered in and saw through me. A glimpse of neighbors milling about their kitchen or the pink hue of a sunset hanging over the rooftops added a wisp of texture in an impermeable landscape, as if Warsaw had been coated with Teflon.

Yet the barbs of the city’s history lay just beneath the surface and occasionally punctured its veneer. Indeed, many of them could be found within a few hundred yards of my room. Across the street, a bunker from the Warsaw ghetto uprising once existed where an apartment building now stands. Around the corner, the remains of Pawiak Prison—a notorious site used by the Gestapo for torture and interrogation—had been converted into a museum. Walking a few blocks north on Karmelicka Street led past the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews (inaugurated in 2013) and the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes before ending near the Umschlagplatz Monument, which marks the site of the “Great Deportation” of a quarter million Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp in the summer of 1942. A few blocks west of my apartment on Nowolipki Street, a large cache of documents from the Oyneg Shabbos secret archive detailing Jewish life and suffering in the ghetto had been unearthed after the war.

Although monuments, museums, and markers of the Warsaw ghetto radiated in all directions from my third-floor window, the past still felt distant and abstract. The contemporary neighborhood bears little resemblance to its pre-war incarnation since the Nazis razed the area in response to the month-long ghetto uprising led by Jewish resistance fighters in 1943. Today, architectural relics of the Cold War set the tone of a bygone era. Posthumous memorial traces of the ghetto often blend in with these monolithic surroundings. The historical reality of the ghetto as a negative space designed to negate the lives of its inhabitants and reduce them to nothing, has no thorny immediacy in this looming, featureless environment.

Looking out the window at the corner of Nowolipki and Karmelicka, I experienced a sense of historical density and paradox rather than the past “coming to life.” Beneath the façade of the apartment buildings that enveloped me, I perceived geologic layers of nothingness—ethereal strata accumulated from successive histories of negation. The once mostly Jewish neighborhood of Muranów collapsed into the ghetto abyss where Polish Jews faced an ever-escalating deprivation of life. Spiraling into the void, a desperate insurgency sought to “negate the negation” imposed by the ghetto as an instrument of annihilation. The Nazis then effaced the ghetto itself and the area reemerged after the war as an embodiment of the Polish People’s Republic behind the Iron Curtain.

When I looked out into the neighborhood, I saw erasure. And people lived in it.

Muranów’s resurrected habitability felt too neat and tidy. Its dull, plodding architecture set the tone of the neighborhood where numbness and predictability might be mistaken for comfort and security. Symbols of historical memory have adapted to its cadence. Even a temporary art installation staged as a disruptive reminder of the Holocaust echoed the anonymous, repetitive abstraction of its surroundings and perennial themes of national martyrdom. Domesticating the former site of the Warsaw ghetto in a monotone timbre does not negate the negation, it erases the erasure.

Confronted with homogenization, my eyes sought rawness and immediacy. I wanted to see some of the rubble and scorched earth that had been plowed over in the postwar era. To clear the ruins and begin life anew on the former site of the ghetto is in part an act of forgetting.

The postwar neighborhood could have been built around part of the ghetto’s remains rather than over them tout court. Debris-hewn vacant lots and other fractures ought to have remained in the landscape to suspend the final realization of the ghetto’s erasure. Beyond the posthumous symbols and institutions of memory that punctuate tourist maps, maintaining an artifactual presence of the ghetto in Muranów would have been an act of justice and a step towards an intentional living with history. Instead, it has long since been replaced by a monolithic and myopic livability.

Life among the ruins, however, often yields strange juxtapositions and selective memories rather than a vanguard of truth and reconciliation.

What does it mean to live near the remnants of a Nazi concentration camp?

It’s a question that has lingered in the recesses of my mind since visiting the Dachau concentration camp in Germany during the final days of a month-long, college graduation trip to Europe. My itinerary had already included many of the hallmarks of a first-time European tour: cosmopolitan cities, Mediterranean beaches, and Swiss chalets. With my remaining time, I had decided to make a stopover in Munich for a few days before boarding an overnight train to Prague, the last destination of my journey. As a history major who had read Primo Levi, researched moral life in the concentration camps, and attended seminars by Holocaust scholars, I felt drawn to the city’s periphery for a closer look at history that I only knew from school. By visiting Dachau, I intended to pay my respects and open myself to the imprint of what remained.

After a day of wandering Munich, I headed for the suburbs on an overcast Saturday morning. A regional train brought me to the town of Dachau, twelve miles northwest of Munich, and I caught a shuttle to the camp from the station. The bus wove through orderly residential neighborhoods lined with terracotta roofs and townhomes painted in soft hues. After rounding a corner, my stomach tightened as a line of guard towers and barbed-wire fence emerged on the horizon. Seeing the camp in the distance while passing through a trim but unremarkable suburbia felt alarming. The contrast suggested a disturbing lack of physical and psychological distance between the town and the camp, the quotidian and the genocidal, the suburban and the fascist, the past and the present.

Living near a Nazi concentration camp like Dachau might entail a refined ability to compartmentalize. Holocaust scholars James Young and Harold Marcuse have each highlighted a convoluted bit of public relations written by Dachau’s mayor for a tourist pamphlet in the 1980s. While recognizing that tourists have come for the camp, the mayor offered the following guidance:

“After your visit, you will be horror-stricken. But we sincerely hope you will not transfer your indignation to the ancient, twelve-hundred-year-old Bavarian town of Dachau, which was not consulted when the concentration camp was built and whose citizens voted quite decisively against the rise of national socialism in 1933. The Dachau Concentration Camp is part of the overall German responsibility for that time. I extend a cordial invitation to you to visit the old town of Dachau only a few kilometers from here. We would be happy to greet you within our walls and to welcome you as friends.”[1]

The interweaving of the town and the camp that I saw from the shuttle bus might have prompted the mayor, had he been sitting beside me, to insist on their mutual exclusion and lament the Nazi cards dealt to an otherwise venerable Bavarian town. The camp was a national relic that could be distinguished from the local history. Would I care to see the town’s medieval church after lunch?

Here, insisting on a sharp distinction between the town and the camp appears to be a symptom of a repressive, even schizophrenic, relationship to the past that visitors are defensively invited to adopt.

Although the town of Dachau cannot be reduced to the camp, it cannot be neatly dissociated from it either. Dachau was the first and longest-running Nazi concentration camp (1933-1945) that began interning political prisoners within a few months of Hitler becoming chancellor. Given its location in a highly populated region of Bavaria, the camp maintained some degree of public visibility even if civilian knowledge of its exact inner workings remained partial. Its presence interpellated popular consent to the Nazi regime, whether in the form of enthusiastic support, fearful compliance, or willful ignorance. Such pressure would have been particularly acute in the town of Dachau where simply going about everyday life served to normalize the camp and the emerging Nazi reality it embodied. By continuing to be itself, the town enabled the camp’s continued existence alongside it.

While the everyday experience of living in the shadow of the Dachau concentration camp remains an open question, over the past twenty years local officials have moved beyond a stance of mutual exclusion and toward a more integrated and transparent approach to the town’s relationship to the camp and the Nazi era. I will highlight two such developments.

In 2005, fifteen former residents of the town of Dachau who perished under Nazi persecution received commemorative Stolpersteine (“stumbling blocks”) outside their former homes. A Stolperstein is a stone with an engraved brass plaque identifying the name, date of birth, date of death (if known), and location of the victim’s death that is usually installed in the sidewalk outside their former residency. Honorees include Jews, Roma, Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses, the mentally disabled, gay men, and groups deemed “socially undesirable” by the Nazis. Since their development by the German artist Gunter Demnig in the early 1990s, over 75,000 Stolpersteine have been installed across more than twenty-five countries to date. In Dachau, the Stolpersteine recipients include Jews, Communists, “criminal types,” and victims of the euthanasia program. The town’s website provides biographical information about each person, a photo of each Stolperstein, and street addresses with links on Google Maps for locating them.

In 2007, town officials installed a “Path of Remembrance” leading from the railway station to the camp gates with historical signage posted along the two-mile route. The historical markers, copies of which can also be found on the town’s website, reveal many historical interconnections between the town and the camp: SS officers lived in houses and villas in the area; some prisoners had to repair local roads as forced labor; a branch line connected the train station to the camp although many arriving prisoners had to make the journey on foot through town; near the end of the war, a train full of dead and dying prisoners from Buchenwald backed up from the camp into town; the day before the U.S. Army liberated Dachau, a group of prisoners and local residents attempted an uprising at the town hall; upon the camp’s liberation, members of the U.S. military forced area residents to view its condition and help bury the dead.

The Stolpersteine and the “Path of Remembrance” in Dachau incorporate memory and memorialization into the landscape of everyday life outside the camp and provide historical leads for visitors. They represent local steps toward truth and accountability that contribute to a larger reckoning with responsibility for the Nazi era by Germany and its accomplices. The attention they have received on the municipal website alongside maps and information about other historical points of interest create a more substantial and balanced appeal to tourists. Still, the updated historical picture remains incomplete. While the “Path of Remembrance” creates tangible links between the town and camp, acts of complicity and collaboration by the residents of Dachau are left to inference. There appears to be a residual hesitancy in assigning guilt to those who did not wear an SS uniform.

My own visit to Dachau preceded these changes by several years. After the unsettling sight of the guard towers emerging behind rooftops of local houses, my visit to the camp felt quiet and pensive. I spent much of my time indoors learning about the camp’s history at the museum located inside a former maintenance building. Since the site had fallen into disrepair for many years after the war, few original structures remained to be seen. A walk around the footprint of the former barracks led to contemporary memorials. Instead of ruins, an unnatural tidiness pervaded the grounds as if one had stepped inside an airless, inert vacuum. Some people still took photos and made video recordings. Had either of them existed at the time, I would have liked to follow the “Path of Remembrance” back into town and track down some of the Stolpersteine. The town of Dachau still had more to say.

If the polished surfaces of Warsaw and the juxtaposition of the two Dachau’s left me seeking the rough edges of the past, I would get more than I bargained for in Lublin.

* * *

In Lublin, Poland, I am appreciated for having an interest in Eastern European history. At least that’s the impression I made on Jacek, my Airbnb host, according to the review he posted on my profile after my three-day visit to his city. His assessment was both accurate and askew in part.

I came to Lublin as the final anchorage point of my two-week journey around central Poland to visit historical sites and memorials featured in Claude Lanzmann’s epic Holocaust film, Shoah.

In Lublin, Holocaust history runs deep. The city served as the main administrative headquarters of the SS during the Final Solution. The Nazis also created a Jewish ghetto near the Old Town and established the Majdanek concentration camp (officially known as Konzentratrionslager Lublin or KL Lublin) in a southeastern neighborhood.

Lanzmann filmed a few brief scenes at Majdanek and the former site of the Lublin ghetto but did not include any of them in the final cut of Shoah. He did, however, feature the extermination camps of Bełżec and Sobibór, both located within a two-hour drive of Lublin. At the time of my visit, Sobibór had been closed for conservation and the construction of a new museum. As a result, the main item on my agenda was a daytrip to Bełżec, eighty miles southeast of Lublin near the Ukrainian border. That left me with an extra day of travel, which I spent at Majdanek.

I arrived in Lublin in the late morning on a bus from Warsaw, just one day after my visit to Treblinka. Having several hours to spare before I would be able to check in at Jacek’s apartment, I stored my suitcase at the tourist office, picked up a handful of maps and brochures, and wandered the Old Town. I ambled through plazas lined with outdoor restaurants and alleyways brightened with mural paintings and mobile art. I found lunch at a bookstore/café and scouted a vegetarian Indian restaurant where I would later return for dinner.

By mid-afternoon, I was settling into my accommodations—a combined living and dining area converted into a guest bedroom with the aid of a futon. The room had a balcony that opened onto a verdant courtyard surrounded by apartment buildings on a quiet side street. My host, Jacek, worked as an official in the city government and as an associate of Marie Curie-Skłodowska University, one of several universities in Lublin. He possessed a polite sense of restraint that I found agreeable the day after my train ride from Warsaw to Małkinia (See #12) and didn’t ask probing questions about my trip. I was happy to play the casual visitor since coming all the way from California to spend an afternoon in Bełżec would require a long explanation.

After noticing my collection of tourist literature, Jacek pointed out sites of local interest in Lublin including the royal castle and an open-air ethnographic museum. He also pulled up videos on my laptop that illustrated the history of Lublin during the medieval and early modern eras and gave me a book of poetry he had published. I received his guidance with curiosity and disclosed my preference for smaller, less touristed cities like Lublin and Łodź that I had developed over the course of my journey. Although neither of us referenced the Holocaust, my tourist pamphlets about Majdanek and Lublin’s Jewish history sat on the table between us. My amenability toward learning about Lublin’s wider history seemed worthy of recognition to Jacek: I was an American interested in Eastern European history.

James Young has written that tourists visiting Poland from abroad often lack broader knowledge of the country’s history beyond World War II and the Holocaust.[2] It’s a telling observation with many implications. From an American standpoint, the history of Poland and other Eastern European countries is often overlooked in favor of their colossal neighbors and erstwhile conquerors, Germany and Russia, and the name “Europe” often evokes England and France first. To possess knowledge of Polish history only in relation to the period of Nazi occupation might be a symptom of the overall narrowness of “Western”-oriented histories.

I had come to Poland as a Holocaust tourist with a very specific itinerary and limited time for broader sightseeing. As my journey progressed, I found myself wanting to explore the cities I passed through in greater depth and connect with their historical and cultural offerings. The reprieve of a vegetarian restaurant proved to be my main source of local life at the end of each day. Based on my time constraints, the pursuit of historical depth in one area meant gliding over the surface of others.

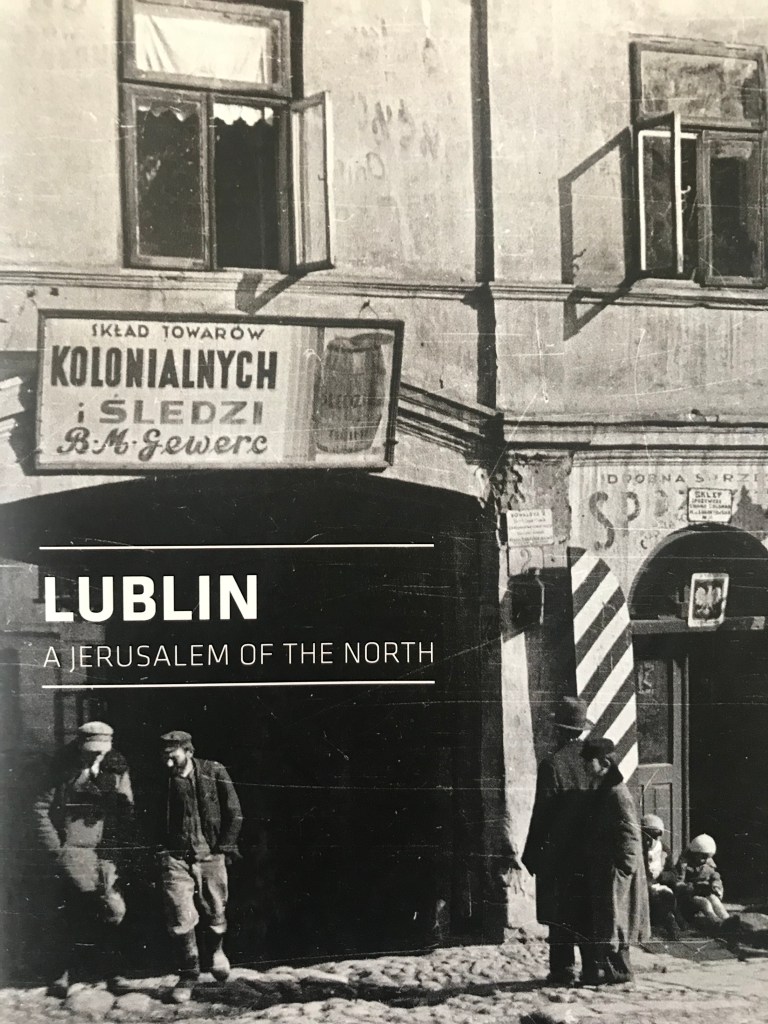

My exchange with Jacek did not alter my immediate itinerary but it did provoke me to seek more information about the history of Lublin and its Jewish community. Both originated in the medieval era, a period when Polish Jews benefited from tolerance and rights granted by the Piast dynasts.[3] In 1569, a series of diplomatic meetings held in Lublin (known as the Union of Lublin) forged the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a massive kingdom that included areas of modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. The Commonwealth drew the largest Jewish population in Europe, which quadrupled in size from 200,000 at its outset to 800,000 in 1795 when the kingdom dissolved.[4] At the time of the Union, Lublin was already a center of Jewish life that included a yeshiva and a Jewish printing press that published the first Talmud in Polish.[5] By the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Lublin’s Jews had established schools, newspapers, social and political organizations, and a hospital. Lublin’s development as a university town led it to become known as the “Jewish Oxford.”[6]

The accolades of Lublin’s Jewish community, however, belie a longer history of instability and unrest in Poland. In 1795, Russia, Prussia, and Austria completed the partitioning of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which divided the Poles across three different countries. Most fell under the domain of the Russian Empire (including Lublin), where the Tsars used military force, censorship, and religious intolerance to maintain power. Polish nationalism grew in the nineteenth century, finding dramatic expression in the January Uprising of 1864, which unsuccessfully attempted to restore the old Commonwealth. Zionism also gained traction among Polish Jews in response to discrimination, settlement restrictions, and pogroms in the Russian Empire.

An independent Polish nation-state emerged from the rubble of World War I, an aftermath that left Germany defeated, the Austro-Hungarian Empire in collapse, and the Soviet Union emerging from the Russian Revolution. While a provisional Polish government had been declared at Lublin in November 1918, the new republic would consolidate over the next two years through the Paris Peace Conference and wars with the Soviet Union and Ukraine. The Second Republic contained parts of modern-day Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, making it one-fifth larger than contemporary Poland. It dissolved in September 1939 with the Nazi invasion and subsequent partitioning of Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union under the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact.

Under wartime occupation, Lublin became a district of the General Government, a Nazi administrative unit in central and eastern Poland, and an epicenter of the Holocaust. According to the final pre-war census conducted in 1931, around 39,000 Jews inhabited Lublin, which represented almost 35% of the total city population.[7] In the spring of 1941, the Nazis established the Lublin ghetto near the city center and blocked it off with barbed wire and street detours. They filled the vacated Jewish homes outside the ghetto with Poles and in turn passed the Polish residences off to Germans.

Nazi operations in Lublin accelerated in the summer and fall of 1941. The SS established arms and clothing factories on the outskirts of the city to support the recent Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and operated them using the forced labor of Jews and prisoners-of-war from nearby concentration camps. In October, Lublin became the administrative headquarters of Operation Reinhard, the SS-led initiative to mass murder all Jews in the General Government using extermination camps at Bełźec, Treblinka, and Sobibór. Ukrainian security forces proved integral to the campaign and received training at the Trawniki labor camp twenty miles outside of Lublin. When the Operation concluded in the fall of 1943, between 1.6 and 1.735 million Jews had perished during its two years of implementation.[8] Eighty percent of the residents of the Lublin ghetto died in the gas chambers of Bełźec in April 1942.[9]

Lublin also became the site of a major concentration camp beginning in the fall of 1941—Konzentrationslager (KL) Lublin—known locally as Majdanek based on the name of the neighborhood where it was located. It started as a camp for Soviet POWs in the fall of 1941 but soon performed multiple functions, from incarcerating Polish peasants whose lands had been confiscated for German settlement to supplying the local SS factories and German industries with forced laborers. Majdanek served as a concentration, extermination, labor, transit, and POW camp during its nearly three years of existence. It was also one of three sites in the Lublin region used for Operation Erntefest (“Harvest Festival”), a mass shooting of Jewish prisoners over a two-day period in November 1943 that resulted in 43,000 deaths.[10] Claude Lanzmann stood before the camera and recounted this event when filming at the camp. The total number of deaths at Majdanek is estimated to be 80,000 with Jews representing 75% of the victims.[11]

The Soviet Army liberated Majdanek in July 1944 during the Battle of Lublin. In the wake of this military victory, the Soviets expanded their bid for control of postwar Poland by installing the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) in Lublin, an organization used to marginalize the sovereignty claims of the Polish resistance movement and the national government-in-exile in London.[12] Meanwhile, the Red Army began imprisoning members of the Polish Home Army at Majdanek. After the war, Soviet-backed authorities turned Majdanek into a museum about Nazi atrocities, Polish victimhood, and Soviet deliverance. It likely marked the beginning of the “victims of fascism” framework that emphasized Polish martyrdom while subsuming Jewish claims of victimhood. This historical outlook defined the Polish People’s Republic and would leave an enduring mark on national memory in Poland.[13]

* * *

I set out for Majdanek on a late Wednesday morning, ascending Lubartowska Street toward Lublin’s Old Town under an overcast sky. Across from the copper-green cupolas of St. John the Baptist Cathedral, I caught a municipal bus heading toward the southeastern outskirts of the city that would reach the camp in two-and-a-half miles. The journey began by tracing a procession of tree-lined streets, apartment complexes, and billboard advertisements as passengers circulated about their daily routines. Just beyond a residential neighborhood an expansive field emerged on the right side of the bus. I noticed wooden guard towers dotting the landscape and signaled for the next stop.

The bus deposited me near the “Monument to Struggle and Martyrdom,” a gnarled monolith that seemed to evoke a demonic rhinoceros in cubist form. Designed by the Polish sculptor Wiktor Tołkin, the monument has stood at the original entrance to the camp since 1969 where it remains a legacy of the Polish People’s Republic. The sculpture’s hulking stance seemed to threaten all who approached it with imminent goring, which led me to anticipate an “in your face” approach to visitor engagement throughout the camp.

Rather than entering Majdanek through Tołkin’s hellish portal, visitors must first negotiate the more prosaic entryway of a parking lot and a visitor center a few hundred meters further southeast. I picked up a map and purchased a few books about the history of the camp in the visitor center, a contemporary structure of glass and concrete run by a staff of young adults. Its youthful airiness felt like a summoning of historical logos in response to the histrionic pathos of Tołkin’s monument. In effect, Majdanek has two entrances that each represent different eras and contrasting approaches to memory. The tension between them would become an underlying theme of my visit as I made my way deeper into the camp.

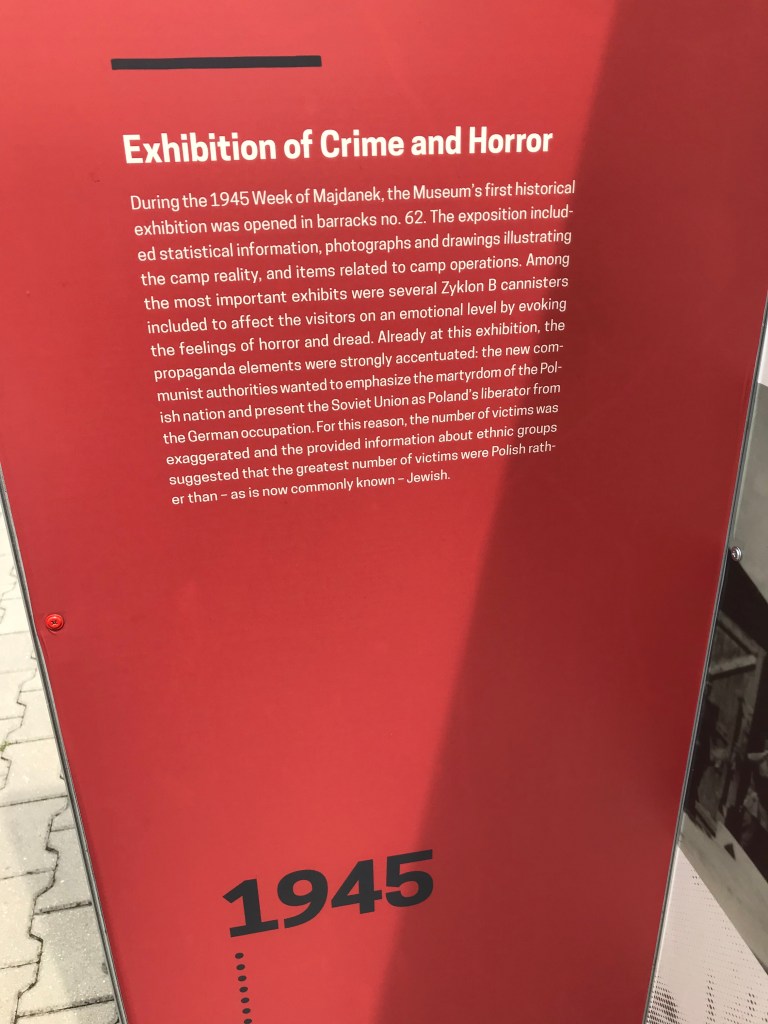

As I embarked on a path that circumnavigated the main historical sites of the camp, my attention first gravitated toward a set of outdoor museum panels about the “Days of Majdanek,” an annual commemorative series held at the camp from 1945 until 2015. Like the visitor center, the signage appeared to be a recent installation and its authors acknowledged that the prevailing political climate in Poland often shaped the “Days of Majdanek” during its sixty-year history. A pro-Soviet standpoint informed its inception, one that emphasized Polish martyrdom and Red Army liberation as Stalin sought to orchestrate the country’s postwar future. It included a historical exhibition inside one of the barracks that displayed cannisters of Zyklon-B to induce “feelings of horror and dread” among visitors to the camp. Through a combination of selective memory and appeals to pathos, the first “Days of Majdanek” aimed to remake Polish national identity in the mold of Soviet loyalty.

The small exhibition about the “Days of Majdanek” could be interpreted as an implicit critique of the nationalist history championed by Poland’s Law and Justice Party (PiS) in recent years. Since gaining control of the presidency and the parliament in 2015, the right-wing, populist PiS has implemented historical revisionism about World War II and the Holocaust supported with laws and institutions to monitor and punish perceived affronts to Poland’s “good name.”[14] The PiS has sought to construct an unequivocally patriotic narrative about Poland that emphasizes national heroism, martyrdom, and innocence during the Second World War. Such an effort developed in part in reaction to decades of historical scholarship documenting instances of Polish involvement in the Holocaust as perpetrators and accomplices—work recast by the PiS as anti-Polish. This reactionary juncture in the politics of memory in Poland gained international notoriety in 2018 when PiS-sponsored legislation amended the role of the Institute of National Remembrance to include the prosecution of public speech that allocates Holocaust responsibility to Poland with exemptions for artistic and academic work. Poland’s “Holocaust law” has been widely condemned as an attack on free speech, historical inquiry, and public memory.

The Soviet-crafted “Days of Majdanek” and the historical engineering of the PiS share common ground. Both have sanctified Polish martyrdom as the historical narrative of World War II in Poland and the foundation of national identity and political loyalty—indeed, of Polishness itself. Both have subsumed the specificity of the Holocaust and the plight of Polish Jews under this narrative framework in varying degrees.

By detailing the origins of the “Days of Majdanek,” the museum curators have historicized the concept of Polish martyrdom and exposed a government-sanctioned narrative about the camp from the Soviet era. This new installation near the camp entrance models critical engagement with history rather than an affirmation of martyrology—a tacit critique of the PiS.

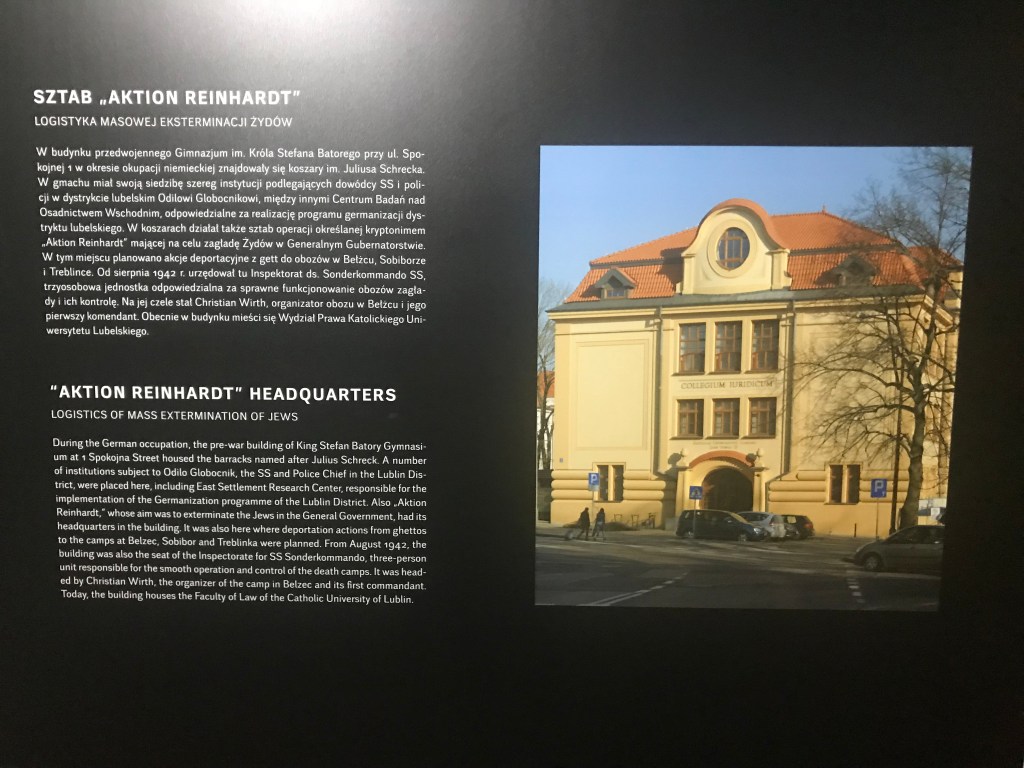

During my visit to Majdanek, I spent most of my time in the newer looking “museum side” of the camp, which consisted of historical exhibitions inside reconstructed barracks. From the “Days of Majdanek” to a history of the camp and a special exhibition about Operation Reinhard, the accounts on display tended to reflect a disinterested and transparent point of view. Past framing of the camp as a site of Polish martyrdom rather than Jewish victimhood received acknowledgment and correction. Sites that had been rebuilt after the war were identified. Signage often quoted the memories of Jewish and Polish prisoners who survived the camp. The exhibit on Operation Reinhard included a photograph of its headquarters, which is now a building on the campus of the Catholic University of Lublin. These historical presentations answered many of my questions about the camp.

Beyond the logos of the “museum side” of the camp, the rest of my visit to Majdanek felt like an escalating spectacle of horror. The gas chambers remained intact and in full view. One barrack contained a mountain of shoes. An excavation of the original camp road revealed broken matzevah from Jewish cemeteries used as cobblestone. The restored crematorium building and its five original furnaces appeared ready to resume operations. The execution ditches used in Operation Erntefest still scarred the landscape.

A gigantic, open-air mausoleum designed by Wiktor Tołkin provided the terrible climax. As part of his “Monument to Struggle and Martyrdom,” it stood 1.1 kilometers across from the monstrous gate, linked together by a straight line called the “Road of Homage and Remembrance.” It resembled a petrified flying saucer. Within it lay an enormous heap of human ash speckled with rocks and dirt from the Nazis’ attempt to conceal their barbaric crimes. The words, “Let our fate be a warning to you” stood above the entrance inscribed in Polish. After the initial shock, I felt revolted by its continued display: I had been lured into a mass grave repurposed as the Polish Golgotha.

I also observed how houses and apartment buildings lined the camp boundaries, making the gas chambers, crematorium, execution ditches, and mausoleum everyday sights for local people as they worked in their yards, sat on their balconies, or cast stray gazes out the window. Had national martyrdom glazed over their eyes like solar eclipse glasses so they could behold their surroundings without burning their eyes?

Tołkin’s ostentatious monuments dwarf the camp and all its historical complexity in favor of a communion with national pathos. Anonymous human ashes—most likely Jewish in origin—have sat for more than five decades inside the mausoleum as the embodiment of Polish martyrdom. While scholars and curators work in earnest to reckon with the historical record, the rhinoceros flares its nostrils and bows its head to charge.

[1] James E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 69. Harold Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 15.

[2] Young, 144.

[3] Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland in Two Volumes, Vol. 1, The Origins to 1795 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 79-80; Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 39-41.

[4] Davies, 240. Lukowski and Zawadzki estimate that the Jewish population in the Commonwealth in 1770 was close to a million. See Lukowski and Zawadzki, 131.

[5] Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia, Vol. I, 1350-1881 (London: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2019), 124, 128-129.

[6] Lublin: A Jerusalem of the North (Lublin: Lublin Municipal Office, n.d.).

[7] Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia, Vol. III, 1914-2008 (London: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2019), 99.

[8] Yitzak Arad, The Operation Reinhard Death Camps: Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, rev. ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018), 440.

[9] Saul Friedlander, The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945 (New York: Harper Collins, 2007), 356.

[10] Arad, 425.

[11] Beata Siwek-Ciupak, Majdanek: A Historical Outline, trans. William Brand (Lublin: Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku, 2014), 28, 30.

[12] Lukowski and Zawadzki, 347-348.

[13] Jörg Hackmann, “Defending the ‘Good Name’ of the Polish Nation: Politics of History as a Battlefield in Poland, 2015-18,” Journal of Genocide Research 20, No. 4 (2018): 590.

[14] See Hackmann, 587-590. See also Timothy Snyder, “Poland vs. History,” The New York Review of Books, May 3, 2016;Alissa Valles, “Scrubbing Poland’s Complicated Past,” The New York Review of Books, March 23, 2018; Jan Grabowski, “The New Wave of Holocaust Revisionism,” The New York Times, January 29, 2022.