The Church of the Birth of the Virgin Mary in Chełmno nad Nerem, Poland

The Church of the Birth of the Virgin Mary in Chełmno nad Nerem, Poland

I hovered the key chain around the dashboard but the car wouldn’t start.

It seemed an inauspicious beginning to my first international car rental and my second full day in Łódź, Poland. After a few moments of dancing the key chain in all directions, I returned to the Avis desk in the lobby of the DoubleTree Hotel to ask for assistance. Despite the sense of ease and guarantee afforded by American brands abroad, the actual start-up of the Renault Clio eluded me. A young sales agent breezed out to the parking lot and revealed that rather than being a keyless ignition, a gray plastic card attached to the key chain had to be inserted into a special slot below the radio.

The car now running, my next feat was setting up the GPS my father had loaned me, the main challenge of which proved to be updating the starting location to the hotel. After another round of fiddling with electronics, I set my course for Chełmno nad Nerem (“Chelmno on the Ner”), about forty-five miles northwest of Łódź. The hour-long drive led me north through Łódź’s rural outskirts before connecting to a westbound toll highway, for which I had prepared a stash of low-denomination złoty bills and an assortment of groszy coins in a brown zippered pouch. The mere prospect of car horns squawking behind me while an automated toll machine denied my credit card or a blank-faced toll collector refused whatever cash I had on hand was enough to inspire preemption.

The rental car: a Renault Clio from Avis

The rental car: a Renault Clio from Avis

After weaving around shipping trucks and trailered farm equipment for many miles, I eventually exited onto a two-lane country road that cut through rolling green fields distantly bound by thick forests. The sparsely populated villages along this route materialized as an occasional roadside building or house that stood in contrast to the digital dot suctioned to the windshield. I might have missed Chełmno nad Nerem all together had it not been for the faded, turquoise church that emerged like a beacon in the pastoral landscape. I slowed the car and a moment later turned into the parking lot of the Muzeum Chełmno.

From Łódź, a quiet drive across an unassuming landscape had brought me to the first Nazi death camp.

Chełmno’s history is somewhat unusual in relation to conventional understandings of the Holocaust. In contrast to the other extermination camps in occupied Poland, such as Treblinka, Bełźec, and Sobibor, the Nazis established Chełmno (known as Kulmhof in German) in the “Wartheland,” a western region carved out for immediate colonization and incorporation into the Third Reich. Since much of this area had previously belonged to the German Empire (1871-1918) and retained a German-speaking population, it became an early site for the attempted realization of Lebensraum (“living space”), Hitler’s racist and imperialist ideology of “Aryan” territorial expansion in Central and Eastern Europe.

Views of the Ner River and surrounding countryside

Views of the Ner River and surrounding countryside

Following the invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Nazis began concentrating Polish Jews in the “General Government,” a special administrative district comprised of four city-based districts: Warsaw, Kraków, Lublin, and Radom. In the early days of the war, the Nazis attempted to forcibly relocate Poles and Polish Jews from the Warthegau to the General Government in order to make room for “Aryan” colonists. This policy gradually shifted towards the systematic extermination of Jews in the Warthegau after the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.

The annihilation phase of the Holocaust began with Einsatzgruppen (“mobile killing units”) shooting Jews en masse in Soviet territories conquered by the Wehrmacht (Nazi Army). Initial references to a larger, “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” surfaced in Nazi ministerial documents that summer. Several months later, Chełmno opened on December 8, 1941 as an extermination site for gassing Jews and Roma Sinti from the Warthegau, including the Łódź ghetto. With Chełmno operational, the subsequent convening of the Wannsee conference on the “Final Solution” on January 20, 1942 served to coordinate and expand a destructive process that had already been set in motion.

The extermination methods used at Chełmno are another unusual feature of the camp. While other death camps relied on gas chambers to conduct mass murder, at Chełmno the Nazis utilized an even more rudimentary method—herding victims into the cargo holds of specially-designed trucks and asphyxiating them with carbon monoxide from the engine exhaust.

The museum entrance in the village of Chełmno

The museum entrance in the village of Chełmno

The “gas vans” at Chełmno developed in response to simultaneous demands for the “liquidation” of Polish mental asylums in Nazi-occupied territories and the alleviation of psychological strain on the Einsatzgruppen from the mass shootings they carried out in the Soviet Union.[1] In the summer and autumn of 1941, the gas vans were the latest result of an ongoing process of invention to increase killing efficiency while shielding the perpetrators from it. They also represent a key intermediary step in the emergence of the “Final Solution” from the initiation of the Tiergarten (T-4) euthanasia program in Nazi Germany to the establishment of death camps in occupied Poland. Indeed, the first commandant of Chełmno, Herbert Lange, had previously led efforts to create “mobile euthanasia units” in the Warthegau. After being “broken in” by the euthanasia program and the Einsatzgruppen, the gas vans became institutionalized at Chełmno.

In addition to the gas vans, the improvisatory character of Chełmno is revealed by its physical organization to which the term “camp” can only be applied provisionally. Rather than carving out a single, fabricated space in the Polish countryside, the Nazis seized and repurposed land and buildings across the region. The village of Chełmno and the nearby Rzuchów forest constituted its two main sites.

A nineteenth-century mansion (referred to as the “castle” in Shoah) served as the focal point of village-based camp operations from 1941 to 1943 (known as the “first period” in the camp’s history). Transports of victims arrived here from Koło, a large town eight miles away with railway connections to Łódź and Poznań, the two largest cities in the Warthegau. Victims would spend the night in the mansion before being instructed to undress for delousing under the auspices of being transferred to a labor camp.[2] Then they would be led to the basement where the gas vans awaited them. Four kilometers away in the Rzuchów forest, their corpses would be unloaded and discarded—at first in mass graves during the early months of the camp’s existence and later in “burning pits” and crematoria.

Efforts to excavate and preserve the foundations of the mansion are ongoing.

Efforts to excavate and preserve the foundations of the mansion are ongoing.

After ten months of operation, mass murder ceased at Chełmno in September 1942 based on its “success” at the total annihilation of Jews in the Warthegau (aside from the Łódź ghetto).[3] Over the next six months, the Nazis concealed traces of the genocide at Chełmno, which included the destruction of the mansion. A modified version of the camp reopened from March 1944 to January 1945 during the “liquidation” of the Łódź ghetto. During this second phase of the camp’s existence, victims would be held overnight in the Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary (next to the former site of the mansion) before being transported to makeshift barracks in the Rzuchów forest and loaded onto the gas vans.

The total number of victims at Chełmno over both periods of operation is estimated to be between 150,000 and 350,000 based on documentation that survived the Nazi cover-up.

Today, a new historical museum sits near the former grounds of the mansion while memorials punctuate the Rzuchów forest and lesser-known sites across the region.

The museum and the visitor center

When I visited Chełmno on a Thursday morning in late June, all was quiet. As I parked the car near the museum, I felt like a lone patron peeking into an empty restaurant. I walked into a small visitor center and purchased a guidebook to the camp. Behind the desk, a young man about my age offered to direct me around the site. His swift gait spoke of a deep knowledge of the camp concealed beneath the routines of tourism and the demands of state-run institutions. He escorted me to a historical exhibit in the museum and later we reunited inside the granary, the only original building that remains in this section of the camp.

During the first period of Chełmno, the granary served as a warehouse for valuables despoiled from the victims. Then in the second period it housed a small cadre of Jewish prisoners used for forced labor. As the Red Army approached in January 1945, it ultimately became the site of a massacre and prisoner revolt. Fleeing Nazi personnel locked the remaining prisoner-workers inside the granary and began leading them out for execution in small batches. A riot ensued and the prisoners killed one of the guards before the Nazis set the building ablaze.

The granary

As we stood inside the granary with its ghostly brick foundations peering through a patchwork of restoration, my guide switched on an overhead projector and an interview with one of the two prisoners who miraculously survived this final ordeal appeared on the wall.

It was Simon Srebnik.

I wrote about him briefly in a previous blog entry about my visit to Oswieçim’s Jewish cemetery, specifically during a discussion of a sequence in Shoah dealing with the erasure of the dead. Standing in the Rzuchów forest, Srebnik recalls the disposal of victims’ ashes in the Ner River during Chełmno’s second period, which initiates a deft segue to the desecration of Jewish cemeteries in Łódź and Oswieçim. Beyond this scene, Srebnik and Chełmno are foundational to Lanzmann’s film—it begins with them, builds from them, and frequently returns to them like an organizing principle.

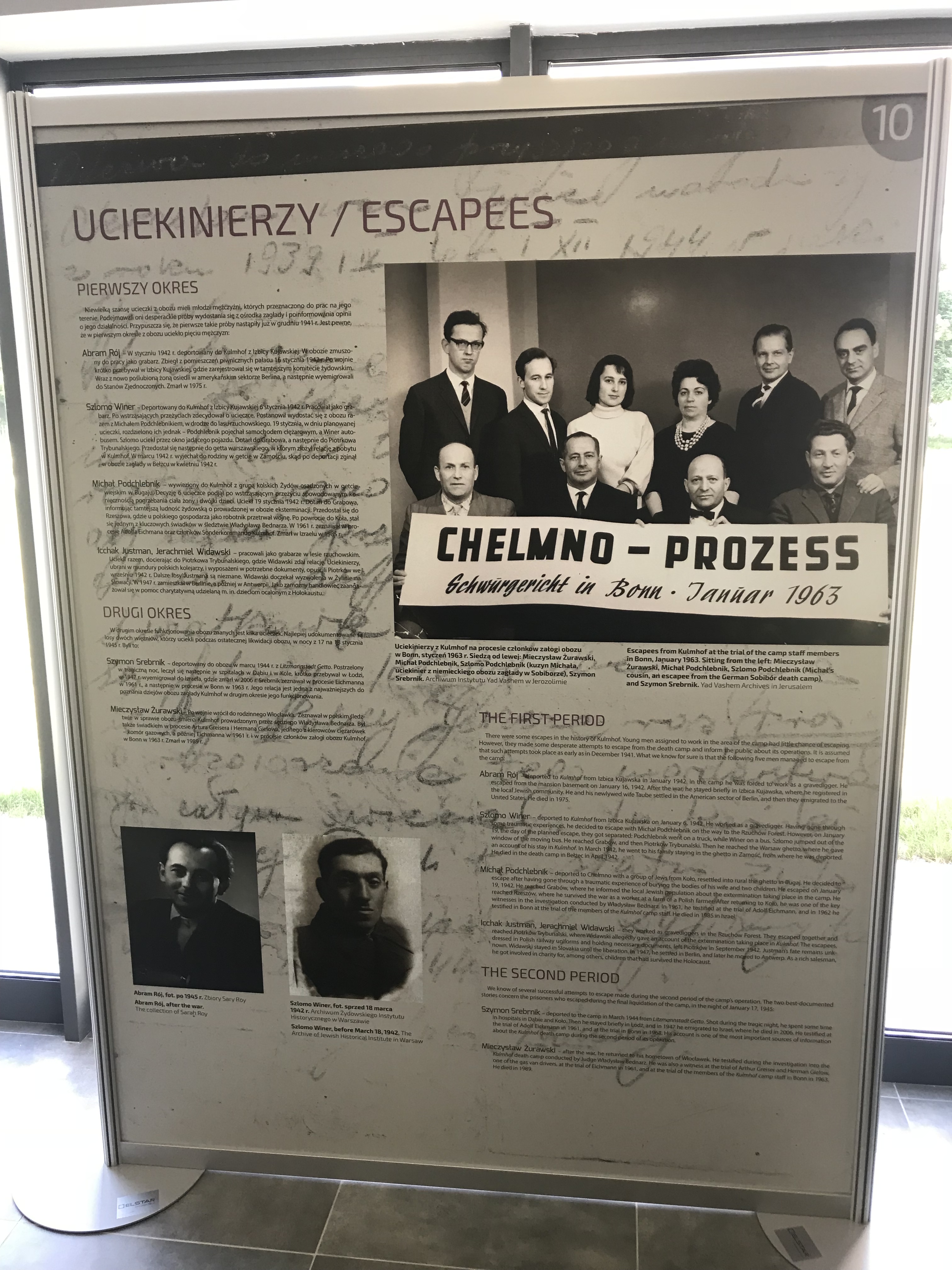

Simon Srebnik can be seen on the bottom right of the group photo.

Simon Srebnik can be seen on the bottom right of the group photo.

The first half of Shoah (designated in the film as the “First Era”) spends a great deal of time in and around Chełmno, including excerpts of the following:

-

On-site interviews with Srebnik in the village and the forest;

-

An interview with Michael Podchlebnik, a Jewish prisoner-worker from Koło who survived the camp’s first period;

-

An interview with Pan Falborski, a Polish worker from Koło who witnessed the deportation of Jews to the camp during its first phase;

-

An interview with Martha Michelsohn, a German woman who settled in Chełmno during the war with her husband, a Nazi schoolteacher;

-

A group discussion with local villagers in front of the church with Srebnik on hand;

-

Interviews with Polish residents in the nearby town of Grabów, whose Jewish community had been murdered at Chełmno;

-

Lanzmann’s reading of a letter from Jacob Schulmann, the rabbi of Grabów who warns his colleagues in Łódź about Chełmno in January 1942;

-

Lanzmann’s reading of a secret Nazi memo from June 1942 that proposes modifications to the gas vans to improve their efficiency.

A path in the Rzuchów forest leading to the main site of Chełmno’s mass graves. Srebnik and Lanzmann are seen walking here in the opening minutes of Shoah.

A path in the Rzuchów forest leading to the main site of Chełmno’s mass graves. Srebnik and Lanzmann are seen walking here in the opening minutes of Shoah. The site of one of Chełmno’s mass graves in the Rzuchów forest

The site of one of Chełmno’s mass graves in the Rzuchów forest The Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary

The Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary The front doors were open but access to the sanctuary was closed.

The front doors were open but access to the sanctuary was closed. “Monument to the Victims of Fascism” (1964)

“Monument to the Victims of Fascism” (1964) Memorial for Austrian Roma Sinti deported to the Łódź ghetto and later murdered at Chełmno (2016)

Memorial for Austrian Roma Sinti deported to the Łódź ghetto and later murdered at Chełmno (2016)

Beautifully weaves together your visit, the film and an augmented history of this monstrous period.

LikeLike